When describing exoplanets that are potentially promising candidates for life, scientists often use the terminology of the “habitable zone.” This is a description of planets in orbit where temperatures, as predicted by the distance from the host star, are not too cold for liquid water to exist on a planetary surface and also not to hot for all the water to burn off.

This planetary sweet spot, which not surprisingly Earth inhabits, is also more casually called the “Goldilocks zone” for exoplanets.

While there is certainly value to the habitable zone concept, there has also been scientific pushback to using the potential presence of liquid water as a primary or singular factor in predicting potential habitability.

There are just too many other factors that can play into habitability, some argue, and a focus on a planet’s distance from its host sun (and thus its temperature regime) is too narrow. After all, several of the objects that just might support life in our own solar system are icy moons quite far from any solar system habitable zone.

With these concerns in the background, an interdisciplinary team of astrophysicists and planetary scientists at the University of California, Santa Cruz has begun to look at a source of heat in addition to suns and tidal forces that might play a role in making a planet habitable.

This source is the heat generated by the decay of long-lived radioactive elements such as uranium, thorium and potassium, which are found in stars and presumably on and in planets throughout the galaxies in greater or lesser amounts.

Using theory and modeling, they have concluded that the abundance of these radioactive elements in a planetary mantle can indeed give important insights into whether life might emerge there.

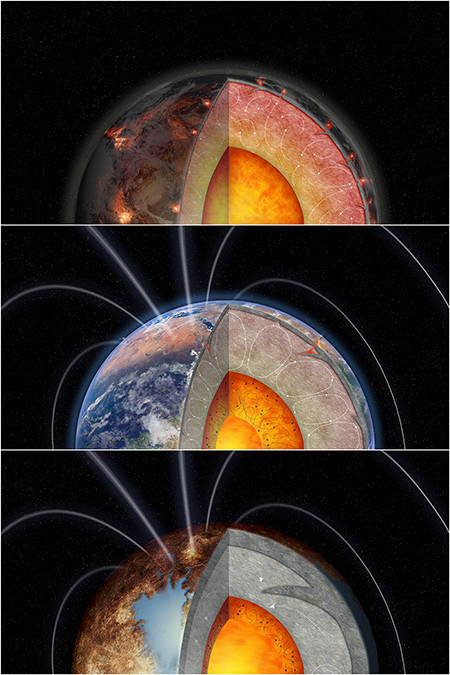

That’s not because the radiogenic heat (produced through radioactive decay) makes the planets warm enough for life per se. It’s rather because internal radiogenic heating may well be necessary for the planet to start plate tectonics that allows the core to cool, to power an internal dynamo and to generate a magnetic field. Magnetic fields such as the one surrounding Earth can protect a planet from solar winds and cosmic rays, while plate tectonics provide a means of modulating the heat of the planet and releasing via volcanoes elements needed to create an atmosphere.

“What we realized was that different planets accumulate different amounts of these radioactive elements that ultimately power geological activity and the magnetic field,” said Francis Nimmo, professor of Earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz and first author of a paper on the new findings, published in Astrophysical Journal Letters. “So we took a model of the Earth and dialed the amount of internal radiogenic heat production up and down to see what happens.”

What they found is that if the radiogenic heating is significantly greater than on Earth, then the planet can’t permanently sustain a dynamo, as Earth has done. This is because most of the thorium and uranium end up in the mantle and too much heat in the mantle acts as an insulator, preventing the molten core from losing heat fast enough to generate the convective motions that produce the magnetic field.

With more radiogenic internal heating the planet also has much more volcanic activity, which could produce frequent mass extinction events.

On the other hand, too little radioactive heat results in no volcanism and a geologically “dead” planet.

“Just by changing this one variable, you sweep through these different scenarios, from geologically dead to Earth-like to extremely volcanic without a dynamo,” said Nimmo, who sees the new paper as “opening a door” to new ideas that other scientists will hopefully want to test and explore.

“Now that we see the important implications of varying the amount of radiogenic heating, the simplified model that we used should be checked by more detailed calculations,” he said in a release.

These illustrations show three versions of a rocky planet with different amounts of internal heating from radioactive elements. The middle planet is Earth-like, with plate tectonics and an internal dynamo generating a magnetic field. The top planet, with more radiogenic heating, has extreme volcanism but no dynamo or magnetic field. The bottom planet, with less radiogenic heating, is geologically “dead,” with no volcanism. (Illustrations by Melissa Weiss)

The dynamo theory referenced by Nimmo describes the process through which a rotating, convecting (rising and falling based on temperature,) and electrically conducting fluid acts to maintain a magnetic field. This theory is used to explain the presence of anomalously long-lived magnetic fields on planets, moons and other bodies. The conductive fluid in the Earth’s geodynamo is liquid iron in the outer core, some 1,800 miles below the surface.

A planetary dynamo has been tied to habitability in several ways, said Natalie Batalha, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics. She leads the Astrobiology Initiative at UC Santa Cruz, which encourages interdisciplinary collaborations like the one that led to this paper. Her program was recently selected as one of eight new NASA astrobiology research centers under the Interdisciplinary Consortia for Astrobiology Research program.

“It has long been speculated that internal heating drives plate tectonics, which creates carbon cycling and geological activity like volcanism, which produces an atmosphere,” Batalha explained in the release. “And the ability to retain an atmosphere is related to the magnetic field, which is also driven by internal heating.”

Absent continued heating, dynamos and the magnetic fields they produce dissipate. Nimmo pointed to Mars as a planet where a dynamo-produced magnetic field was initially present and created an atmosphere that allowed liquid water to flow on the surface (and to just possibly support life) for hundreds of millions of years. But when the dynamo fell apart, for reasons currently unknown, the atmosphere was stripped away and the planet became the arid and inhospitable place we see now.

While all rocky planets are formed with vast primordial heat inside, that heat gradually diminishes. So the geological and electro-magnetic future of planets, or some planets, become increasingly determined by the presence, or absence, of heat-producing radioactive elements, Nimmo said. Some radioactive isotopes that play important roles are relatively short-lived, such as aluminum and magnesium which decay over millions of years, and then there’s uranium, thorium and potassium that decay (and give off heat) over billions of years.

While all these radioactive elements and their compounds are found on the earth’s surface or crust, the most important concentrations are scattered through the much larger mantle beneath it where the planet-molding activity takes place, Nimmo said.

This hypothesis that habitability is related to radiogenic heating, he told me, can also apply to rocky planets substantially larger than Earth.

Another aspect of the radiogenic heat story involves how those very heavy elements are formed in the galaxies, and the implications of how and where they are forged.

Early explanations of how uranium, thorium et al were formed focused on supernovae, the explosive brightening of a star in which the energy radiated by it increases by a factor of ten billion. A supernova explosion occurs when a star has burned up all its available nuclear fuel and the core collapses catastrophically. It is well established that key elements such as carbon and sulfur are produced in those massive explosions, and heavy radioactive elements were theorized to be formed in that cauldron as well.

More recently, scientists have focused instead on the mergers, or collisions, of neutron stars as the source. In the aftermath of the 2017 detection of a neutron star collision (and creation of a subsequent gravitation wave) by the LIGO instruments, the neutron star origins of very heavy elements became more widely embraced. That’s because the collision was found to produce jets of radiation and of heavy elements.

Neutron stars are the collapsed cores of massive super-giant stars, and have radii on the order of 10 miles but with a mass greater than that of our sun. They are so dense that a matchbox containing neutron-star material would have a weight of approximately 3 billion tons.

But neutron star mergers or collisions, which have been a focus of research by co-author Enerico Ramirez-Ruiz of UC Santa Cruz, are known to be quite rare. This has implications for the question of the radiogenic makup of stars and planets throughout the cosmos.

“We would expect considerable variability in the amounts of these elements incorporated into stars and planets, because it depends on how close the matter that formed them was to where these rare events occurred in the galaxy,” said co-author Joel Primack, a professor emeritus of physics at UC Santa Cruz, in the release.

While it is not possible now, and likely well into the future, to detect long-lived radioactive elements on and in exoplanets, there are ways to make informed inferences.

Astronomers can use spectroscopy to measure the abundance of different elements in stars, and the compositions of planets are expected to be similar to those of the stars they orbit. Both uranium and thorium do not show up well in stellar spectra, but the element rare earth element europium does.

Europium is created by the same process that makes thorium and uranium, so using europium as a tracer is possible to study the variability of those elements in our galaxy’s stars and planets.

The Astrophysical Journal paper concludes:

“It is tempting to speculate that the Earth is habitable in part because it possesses a ‘Goldilocks’ concentration of radiogenic elements: high enough to permit long-lived dynamo activity and plate tectonics, but not so much that extreme volcanism and dynamo shutoff occur.”

“As yet, however, our understanding of the complicated feedbacks involved is too rudimentary to make such a definitive conclusion; more detailed calculations, and better characterization of the radiogenic element abundances in planet-hosting stars, are both required.”