For NASA to extend its space science missions well past their original lifetime in space has become such a commonplace that it is barely noticed.

The Curiosity rover was scheduled to last on Mars for two years but now it has been going for a decade — following the pace set by earlier, smaller Mars rovers. The Cassini mission to Saturn was extended seven years beyond it’s original end date and nobody expected that Voyager 1, launched in 1977, would still flying out into deep space and sending back data 45 years later.

The newest addition to this virtuous collection of over-achievers is the Juno spacecraft, which arrived at Jupiter in 2016. Its prime mission in and around Jupiter ended last year and then was extended until 2025, or beyond.

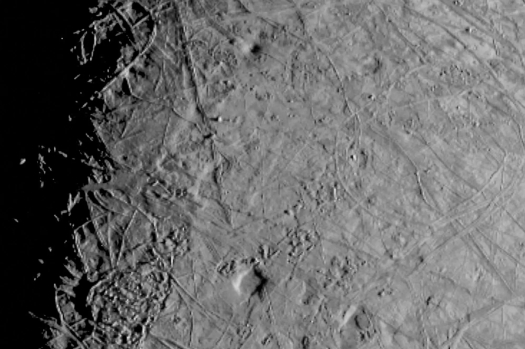

And now we have some new and intriguing images of Jupiter’s moon Europa thanks to Juno and its extension.

Traveling at a brisk 14.7 miles per second, Juno passed within 219 miles of the surface of the icy moon on Thursday and images from the flyby were released today (Friday.) That gave the spacecraft only a two-hour window to collect data and images, but scientists are excited.

“It’s very early in the process, but by all indications Juno’s flyby of Europa was a great success,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, in a NASA release.

“This first picture is just a glimpse of the remarkable new science to come from Juno’s entire suite of instruments and sensors that acquired data as we skimmed over the moon’s icy crust.”

Candy Hansen, a Juno co-investigator who leads planning for the Juno camera at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, called the released images “stunning.”

“The science team will be comparing the full set of images obtained by Juno with images from previous missions, looking to see if Europa’s surface features have changed over the past two decades,” she said.

During the flyby, the mission collected what will be some of the highest-resolution images of the moon (0.6 miles per pixel) taken so far and obtained valuable data on Europa’s ice shell structure, interior, surface composition, and ionosphere, in addition to the moon’s interaction with Jupiter’s magnetosphere.

These observations from Juno, along with data collected decades ago by the previous Voyager 2 and Galileo, missions will be useful preparation for NASA’s upcoming NASA’s Europa Clipper mission. Scheduled to arrive at Europa in 2030, it will study the moon’s atmosphere, surface, and interior – with a goal to determine whether it might be habitable and to better understand its global subsurface ocean, the thickness of its ice crust. It will also search for possible plumes that may be venting subsurface water into space.

Juno’s close-up views and data from its Microwave Radiometer (MWR) instrument will provide new details on how the structure of Europa’s ice varies beneath its crust. Scientists can use all this information to generate new insights into the moon, including data in the search for regions where liquid water may exist in shallow subsurface pockets.

Europa, which is almost as large as our moon, is known to have a large subsurface ocean that many scientists see as perhaps the most plausible environment in the solar system for extraterrestrial life. The Europa Clipper mission was selected in large part because of that possibility.

The easily visible fractures in the ice cover – created by the stress of tidal forces — were early signs of a possible Europan ocean under the ice. Later magnetic field measurements pointed to a salty ocean, adding to the scientific consensus that there was a large subsurface ocean.

The European Space Agency will also be sending a spacecraft to the Jovian system around the same time that the Europa Clipper will be flying there. The JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission, scheduled to launch in 2023 and reach Jupiter in 2031, will orbit or fly by three of the icy moon of Jupiter — Europa, Callisto and Ganymede.

All three of these moons have subsurface oceans that contain significantly more water than the oceans of Earth.

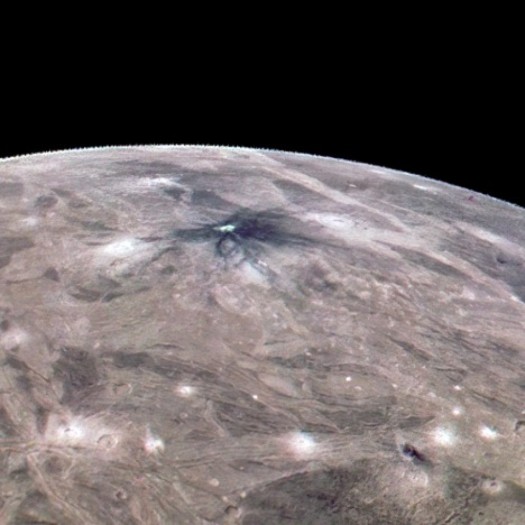

The Juno spacecraft has already flown past Ganymede and will explore Io, a volcanic moon, in 2023 and 2024. Juno’s investigation of Io addresses many science goals identified by the National Academy of Sciences for a future Io explorer mission.

The moon Ganymede is larger than the planet Mercury and is the only moon in the solar system with its own magnetosphere – a bubble-shaped region of charged particles surrounding the celestial body. Juno passed at at 645 miles over the moon’s surface.

Juno principal investigator Bolton said that by flying so close to the moon, they brought “the exploration of Ganymede into the 21st century.”

He said that flyby, like the one of Europa, complemented “future missions with our unique sensors and helping prepare for the next generation of missions to the Jovian system – NASA’s Europa Clipper and ESA’s [European Space Agency’s] JUpiter ICy moons Explorer [JUICE] mission.”

All four of the new Juno images of Europa are available on Juno’s website. While the images have a yellowish-brown color to them, the moon would look light natural color because of its ice covering. The Juno camera was placed on the spacecraft to take images the public would find compelling and was not primarily designed as a scientific instrument.

The Clipper, however, will definitely have cameras designed for scientific heavy lifting.