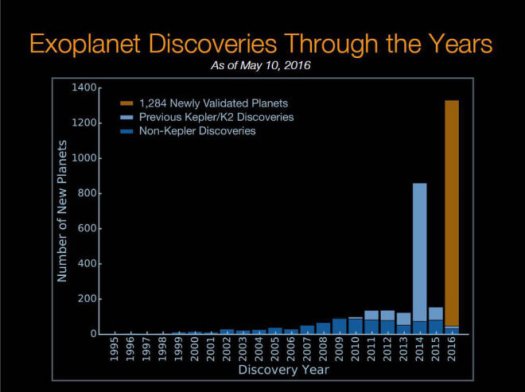

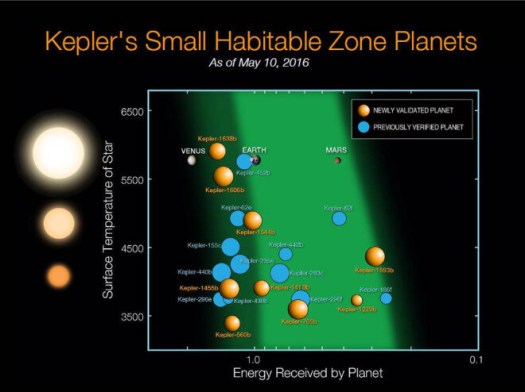

In the biggest haul ever of new exoplanets, scientists with NASA’s Kepler mission announced the confirmation of 1,284 additional planets outside our solar system — including nine that are relatively small and within the habitable zones of their host stars. That almost doubles the number of these treasured rocky planets that orbit their stars at distances that could potentially support liquid water and potentially life.

Prior to today’s announcement, scientists using Kepler and all other exoplanet detection approaches had confirmed some 2,100 planets in 1,300 planetary systems. So this is a major addition to the exoplanets known to exist and that are now available for further study by scientists.

These detections comes via the Kepler Space Telescope, which collected data on tiny decreases in the output of light from distant stars during its observing period between 2009 and 2013. Those dips in light were determined by the Kepler team to be planets crossing in front of the stars rather than impostors to a 99 percent-plus probability.

As Ellen Stofan, chief scientist at NASA Headquarters put it, “This gives us hope that somewhere out there, around a star much like ours, we can eventually discover another Earth.”

(NASA Ames/W. Stenzel; Princeton University/T. Morton)

The primary goals of the Kepler mission are to determine the demographics of exoplanets in the galaxy, and more specifically to determine the population of small, rocky planets (less than 1.6 times the size of Earth) in the habitable zones of their stars. While orbiting in such a zone by no means assures that life is, or was, ever present, it is considered to be one of the most important criteria.

The final Kepler accounting of how likely it is for a star to host such an exoplanet in its habitable zone won’t come out until next year. But by all estimations, Kepler has already jump-started the process and given a pretty clear sense of just how ubiquitous exoplanets, and even potentially habitable exoplanets, appear to be.

“They say not to count our chickens before they’re hatched, but that’s exactly what these results allow us to do based on probabilities that each egg (candidate) will hatch into a chick (bona fide planet),” said Natalie Batalha, co-author of the paper in the Astrophysical Journal and the Kepler mission scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center.

“This work will help Kepler reach its full potential by yielding a deeper understanding of the number of stars that harbor potentially habitable, Earth-size planets — a number that’s needed to design future missions to search for habitable environments and living worlds.”

Batalha said that based on observations and statistics the Kepler mission has produced so far, we can expect that there are some 10 billion relatively small, rocky (and potentially habitable) planets in our galaxy. And with those numbers in mind, she said, the closest is likely to be in the range of 11 light years away.

She said that all of the exoplanets found in habitable zones are in the “exoplanet Hall of Fame.” But she said two of the newly announced planets in habitable zones, Kepler 1286b and Kepler 1628b, joined two previous exoplanets of particular interest either because of their size (close to that of Earth) or their Earth-like distance from suns rather like ours.

Batalha said a new and finely-tuned software pipeline has been developed to better analyze the data collected during those four years of Kepler observations. Asked if the final Kepler catalogue of exoplanets, expected to be finished next summer, would increase the current totals of exoplanets found, she replied: “It wouldn’t surprise me if we had hundreds more to add.”

Once the Kepler exoplanet list is updated, scientists around the world will begin to study some of the most surprising, enticing, and significant finds. Kepler can tell scientists only the location of a planet, its mass and its distance from the host star. So the job of further characterizing the planets — and ultimately determining if any are indeed potentially habitable — requires other telescopes and techniques.

Nonetheless, Kepler’s ability to give scientists a broad picture of the distribution of exoplanets — to find large numbers of them rather than, as pre-Kepler, one or two at a time — has been revolutionary. It has also been remarkably speedy, thanks in large part to an automated system of analyzing transit data devised by Tim Morton, a research scientist at Princeton University,

“Planet candidates can be thought of like bread crumbs,” Morton said in a NASA teleconference. “If you drop a few large crumbs on the floor, you can pick them up one by one. But, if you spill a whole bag of tiny crumbs, you’re going to need a broom. This statistical analysis is our broom.”

Kepler identified another 1,327 candidates that are very likely to be exoplanets, but didn’t meet the 99 percent certainty level required to be deemed an exoplanet.

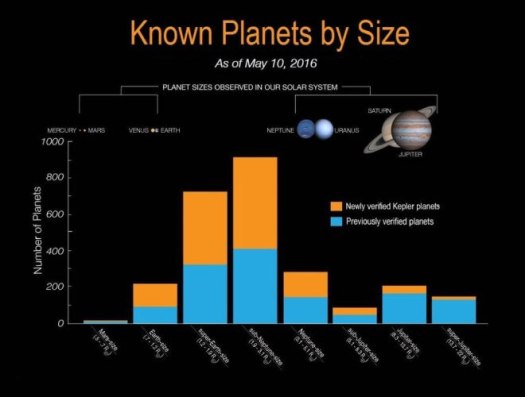

A large percentage of the newly confirmed planets are either “super-Earths” or “sub-Neptunes” — planets in a size range absent in our solar system. Initially, the widespread presence of exoplanets of these dimensions was a puzzle to the exoplanet community, but now the puzzle is more why they are absent in our system.

Despite the abundance of these exoplanets — which are believed to be mostly gas or ice giants — scientists are convinced there are considerably more rocky, even Earth-sized planets that current telescopes can’t detect.

The primary Kepler mission focused on one small piece of the sky — about 0.25 percent of it — and a distant part at that. It watched nonstop for transiting planets in that space for four years, watching unblinkingly at some 150.000 stars. The result has been a treasure trove of data that can then be broadened statistically to tell us about the entire galaxy.

So Kepler has revolutionized our understanding of the galaxy and what’s in it, and has proven once and for all that exoplanets are common. But the individual planets that it has detected are unlikely to be the ones that allow for breakthroughs in terms of sniffing out what chemicals are in their atmospheres — an essential process for determining if a potentially habitable planet actually has some of the ingredients for life.

This is because Kepler was looking far into the cosmos, between 600 and 3,000 light years from our sun. While the telescope identified almost 5,000 “candidate planets” during its four years of primary operation — and now more than 2,200 confirmed planets — the planets are generally considered too distant for the more precise follow-up observing needed to understand their atmospheres and chemical make-ups.

This work will fall to ground-based telescopes looking at nearer stars, and to future generations of American and European space telescopes using the transit method of detection pioneered by Kepler. (See graphic above.) The next space satellite in line is NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which is scheduled to launch in 2017 and will focus on planets orbiting much closer and brighter stars. The long-awaited James Webb Space Telescope, due to launch in 2018, also has the potential to study exoplanets with a precision, and in wavelengths, not available before.

NASA has begun development of the more sophisticated Wide Field Infrared Survey Satellite (WFIRST) to further exoplanet research in the 2020s, and has set up formal science and technology definition teams to plan for a possible flagship exoplanet mission for the 2030s. That mission would potentially have the power and techniques to determine whether an exoplanet actually has the components, or the presence, of life.