Imagine counting all the people who have ever lived on Earth, well over 100 billion of them.

Then imagine counting all the planets now orbiting stars in our Milky Way galaxy , and in particular the ones that are roughly speaking Earth-sized. Not so big that the planet turns into a gas giant, and not so small that it has trouble holding onto an atmosphere.

In the wake of the explosion of discoveries about distant planets and their suns in the last two decades, we can fairly conclude that one number is substantially larger than the other.

Yes, there are many, many billions more planets in our one galaxy than people who have set foot on Earth in all human history. And yes, there are expected to be more planets in distant habitable zones as there are people alive today, a number upwards of 7 billion.

This is for sure a comparison of apples and oranges. But it not only gives a sense of just how commonplace planets are in our galaxy (and no doubt beyond), but also that the population of potentially habitable planets is enormous, too. “Many Worlds,” indeed.

It was Ruslan Belikov, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley who provided this sense of scale. The numbers are of great importance to him because he (and others) will be making recommendations about future NASA exoplanet-finding and characterization missions based on the most precise population numbers that NASA and the exoplanet community can provide.

Natalie Batalha, Mission Scientist for the Kepler Space Telescope mission and the person responsible for assessing the planet population out there, sliced it another way. When I asked her if her team and others now expect each star to have a planet orbiting it, she replied: “At least one.”

I caught up with Belikov, Batalha and several dozen others intimately involved in cataloguing the vast menagerie of exoplanets at a “Hack Event” earlier this month at Ames. The goal of the three-day gathering was to find ways to improve the already high level of reliability and completeness regarding planets identified by Kepler.

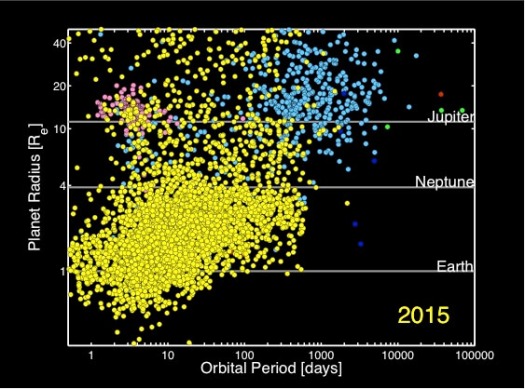

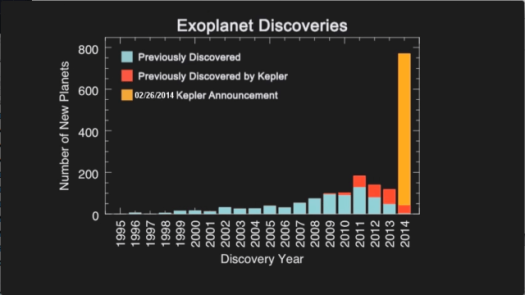

It also provided an opportunity to learn more about how, exactly, these scientists can be so confident about the very large numbers of exoplanets and habitable zone exoplanets they describe. After all, the total number of confirmed exoplanets is a bit under 2,000 – a majority found by Kepler but hundreds of others by pioneering astronomers using ground-based telescopes and very different techniques. Kepler has another 3,000 planet candidates that scientists are in the process of analyzing and most likely confirming, but still. Four thousand is minuscule compared with two hundred billion.

Not everyone completely agrees that we’re ready to estimate such large numbers of exoplanets—suggesting that we need more data before making such important estimates — but the community consensus is that their extrapolations from current data are solid and scientific. And here is why:

The Kepler telescope looks out at a very small portion of the sky with a limited number of stars – about 190,000 of them during its four year survey. And it identifies planets based on the tiny dimming of stars when an object (almost always a planet) crosses between the star and the telescope.

By identifying those 4,000-plus confirmed and candidate planets over four years, Kepler infers the existence of many, many more. As Batalha explained, a transit of the planet is only observable when the orbit is aligned with the telescope, and the probability of that alignment is very small. Kepler scientists refer to this as a “bias” in their observations, and it is one that can be quantified. For example, the probability that an Earth-Sun twin will be aligned in a transiting geometry is just 0.5%. For every one that Kepler detects, there are 200 others that didn’t transit simply because of the orientation of their orbits.

Then there’s the question of faintness and reliability. Kepler is looking out at stars hundreds, sometimes thousands of light years away. The more distant a star, the fainter it is and the more difficult it is to gather measurements of –and especially dips in — brightness. When it comes to potentially habitable, Earth-sized planets, Batalha said that only 10,000 to 15,000 of the stars observed are bright enough for planets to be detectable even if they do transit the disk of their host star.

Here’s why: Detecting an Earth-sized planet would be roughly equivalent to capturing the image of a gnat as it crosses a car headlight shining one mile away. For a Jupiter-size planet, the bug would grow to only the size of a large beetle.

Add this bias to the earlier one, and you can see how the numbers swell so quickly. And since Kepler’s mission has been to provide a survey of planets in one small region – and not a census – this kind of statistical extrapolation is precisely what the mission is supposed to do.

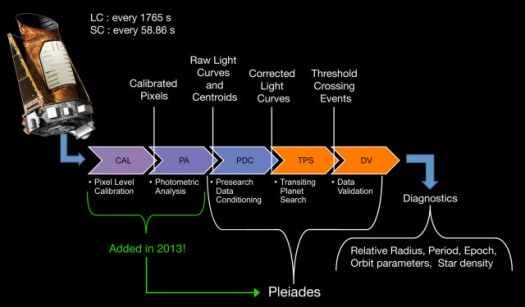

There are numerous other detecting challenges posed by the dynamics of exoplanets, stars and the great distances. But then there are also innumerable challenges associated with the workings of the 95 megapixel CCD array that is collecting light for Kepler. “Sensitivity dropouts” caused by those cosmic rays, horizontal “rolling bands” on the CCDs caused by temperature changes in the electronics, “optical ghosts” from binary stars that create false signals of transits on nearby stars — they are some of the many instrument artifacts that can be mistaken as a drop in light coming from a planet. Kepler’s data processing pipeline, much of which has been transferred over to the NASA Ames supercomputer, has the job of sorting all this out.

Adding to the challenge, said Jon Jenkins, a Kepler co-investigator at Ames and the science lead for the pipeline development, is that the stars viewed by Kepler turned out to be themselves “noisier” than expected. Stars naturally vary in their overall brightness, and the data processing pipeline had to be upgraded to account for that changeability. But that stellar noise has played a key role in keeping Kepler from seeing some of the small planet transits that the team hoped to detect.

What the Hack event and other parallel efforts are doing is finding ways to, as Jenkins put it, “dig into the noise…to move towards the hairy edge of what our data can show.” The final goal: “To come up with the newest, best washer we can to clean the data and come out with an improved catalog of sparkling planets.”

All the data that will come from the primary Kepler mission, which came to a halt in the summer of 2013, has been collected and analyzed already on a first round. But now the entire pipeline of data is going to be reprocessed with its many improvements so the researchers can dig deeper into data trove. Batalha said they hope to find planets – especially Earth-sized planets – this way.

One of the key techniques to measure the performance of Kepler’s analysis pipeline is to inject fake transit signals into the data and see if it picks up their presence.

As Batalha explained, this provides another way to gauge the biases in the system, its efficiency at detecting the planets that it could and should see. “If we inject 100 fake things into the pipeline and find 90 of them, that’s means we’re 90 percent complete.” She said the number would then be worked into the calculations of how many planets are out there, and how many of certain sizes will be caught and missed.

So the Hack Event, which brought together astrophysicists, planetary scientists and computer hakers, was designed to come up with ways to improve Kepler’s completeness (seeing everything there to be seen) and reliability (the likelihood that the signal comes from a planet and not an instrument artifact or non-planetary phenomena in space). By computing both the completeness and reliability, scientists are confident that they can eliminate the observation biases and transform the discovery catalog into a directory of actual planets.

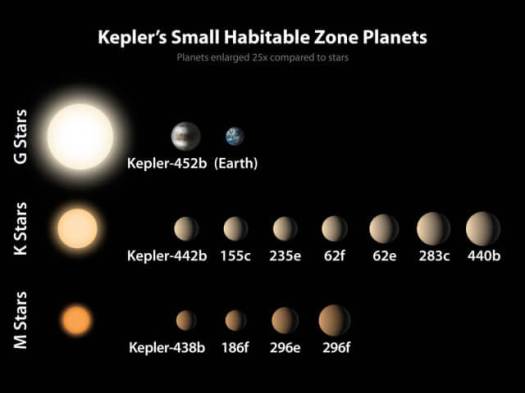

This is one of the key accomplishments of the Kepler mission – making it scientifically possible to say that there are billions and billions of planets out there. What’s more, the increased power of Kepler allowed for the discovery of smaller planets, which are now known to make up the bulk of the exoplanets. And while the number of Earth-sized planets detected in that habitable zone is small – around thirty – that’s still quite a remarkable feat. And remember, Kepler is looking at but one small sliver of the sky.

Why does it matter how many exoplanets are out there, how many are rocky and Earth-sized, and how many within habitable zones? The last twenty years of exoplanet hunting, after all, has made clear that there are an essentially infinite number of them in the universe, and untold billions in our galaxy.

The answer lies in the insatiable human desire to know more about the world writ large, and how and why different stars have very different solar systems. But more immediately, there’s the need to know how to best design and operate future planet-finding missions. If the goal is to learn how to characterize exoplanets – identify components of their atmospheres, learn about their weather, their surfaces and maybe their cores – then scientists and engineers need to know a lot more about where planets generally, and some specifically, can be found. And those planet demographics just might open some surprising possibilities.

For instance, Belikov and his Ames colleague Eduardo Bendek have proposed a NASA “small explorer” (under $175 million) mission to launch a 30-to-45 centimeter mirror designed to look for Earth-sized planets only at our nearest stellar neighbor, Alpha Centauri. That’s as small a telescope as you can buy off-the-shelf.

Alpha Centauri is a two-star system, and until recently researchers doubted that binaries like it would have orbiting planets. But Kepler and other planet hunters have found that planets are relatively common around binaries, making Alpha Centauri a better target than earlier imagined.

To make it a truly viable project, ACESat – the Alpha Centauri Exoplanet Satellite – requires something else: a scientifically sound estimate of the likelihood that any star in our galaxy would have an Earth-sized planet in its system. Estimates so far have ranged from 10 percent to 50 percent, but Belikov said newer data is encouraging.

“If that number becomes more firm and approaches 50 percent, then an Alpha Centauri-only mission makes a great deal of sense,” he said. “For a small investment, we could have a real possibility of detecting a planet very close by.”

Intriguing, and an insight into how new space missions are designed based on the science already completed. Both NASA and the European Space Agency have plans to launch three significant exoplanet missions within the decade, and the powerful James Webb Space Telescope will launch in 2018 with some known and undoubtedly some not yet understood capabilities for exoplanet discovery. And perhaps most important, NASA is about to study how a potential mission in the 2030s could be designed with the specific purpose of directly imaging exoplanets – the gold standard for the field. All are being designed based on current exoplanet understandings, including the abundance calculations enabled by the Kepler mission’s observations.

Future posts will dig deeper into a fair number of the subjects raised here, but for now this much is clear: Our galaxy has many billions of planets, and the process of detecting them is robust and on-going, the process of characterizing them has begun, and all the signs point towards the presence of enormous numbers of planets in habitable zones that, in the biggest picture at least, could possibly support life.