In a solar system far, far away, life of some sort is just waiting to be found. Or so the world of astrobiology sure hopes it is.

The new player in the astrobiology world, now called the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), is planned to launch in the 2040s if all goes well. While it’s possible that some sign of extraterrestrial biology will be found earlier via the upcoming Europa Clipper mission, the Mars Sample Return or other platforms already in place, the Habitable World Observatory is in an astrobiology class of its own.

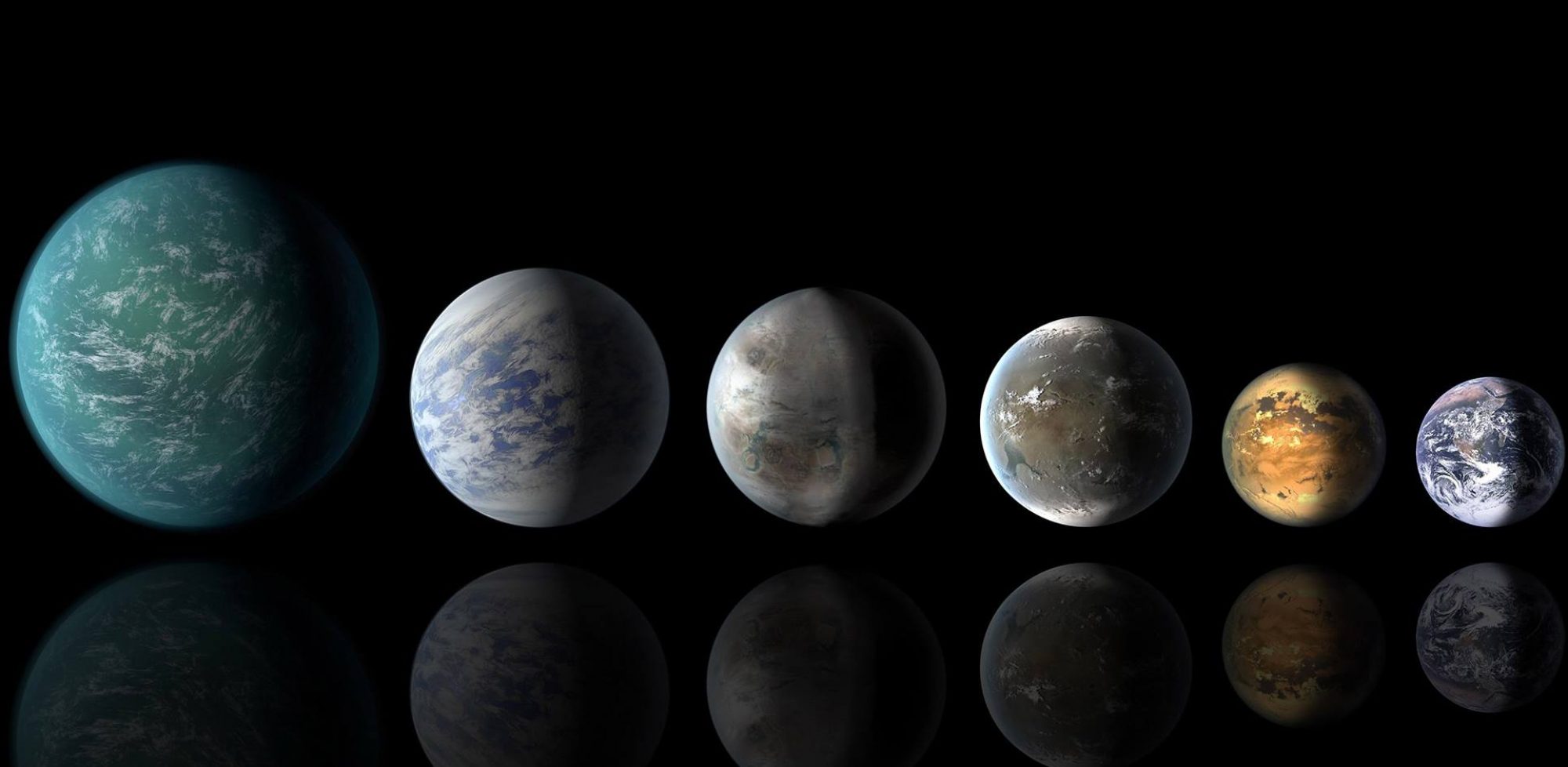

It will be the first NASA Flagship Grand Observatory to be designed specifically to search for signs of life on Earth-sized planets many light-years away. The proposed technology will allow scientists to not only read the chemical composition of atmospheres for signs of biology, but also to potentially characterize planetary surfaces as well.

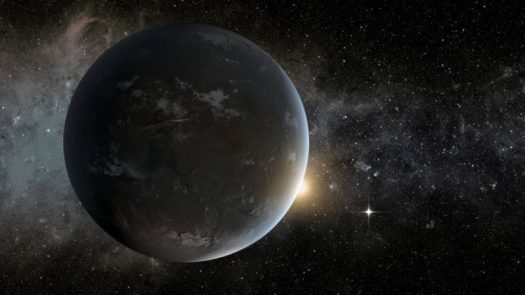

And the plan is for the observatory to stare at these small exoplanets directly, like a camera that images a scene in the distance. But here it’s at an entirely unprecedented distance and with an additional extreme difficulty factor — the blinding light of the star that the planet orbits.

Technology to block that light and to create an observatory stable enough to focus on a tiny dot in the extreme distance is an unprecedented challenge. But NASA has already created a science and technology program to dig deep into the difficulties and possible payoffs from what might become the most ambitious project that NASA (and partners) have undertaken.

To better understand the process by which this super grand observatory will (hopefully) become a reality, I spoke with Shawn Domagal-Goldman, Program Scientist, for the Great Observatory Maturation Program (GOMAP). He and other scientists and engineers have assembled two working committees to examine the knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns and more of the Habitable Worlds Observatory project.

That this process has already started two decades before the observatory is likely to launch gives some insight into its complexity, as well as the agency’s concerted efforts to build it with extensive pre-planning to avoid the cost overruns and delays that have come along with some other ambitious NASA projects. The James Webb Space Telescope, for instance, was frustratingly over budget and delayed for years, although its ability to see deeply into the sky and to characterize some exoplanet atmospheres has certainly proven worth the wait.

As Domagal-Goldman explained it, the Habitable Worlds Observatory was strongly recommended in the 2020 National Academy of Sciences Decadal Survey in astronomy and astrophysics, as was the technology and science maturation projects now underway.

The Academy did not specify how the mission should be developed, but it did set these general goals that the GOMAP team is now working to piece together:

- The space telescope should be able to identify and study 25 Earth-sized exoplanets and determine if they are habitable and potentially inhabited.

- The project should cost in the $10-$11 billion range, which is around what the Webb Telescope cost.

- The development of new technologies and refining of science goals will likely lead to a launch in the 2040s.

- The HWO will be the first NASA Grand Observatory with a central focus of the search life beyond Earth. Current space and ground observatories are certainly pushing the envelope of biology in astrobiology, but they have not been developed with instruments explicitly designed to search for extraterrestrial life. HWO will be.

- The mission recommended by the Academy and adopted by NASA is a compromise of sorts between two Grand Observatory proposals dedicated to astrobiology. One called for a segmented telescope mirror that can fold up and then be deployed in space (like the one used by the Webb Telescope) that would be somewhere between 8 meters (26 feet) and 15 meters (almost 50 feet) in diameter — a much larger mirror than anything in space. The other proposal called for a mirror or 4 meters (13 feet.) The mirror size recommended by the Academy is in the 6-to-6.5 meter (20 feet) range.

- The observatory will rely on “direct imaging” — where the telescope stares straight at the planet rather than looking for indirect effects. The observatory will need a coronagraph to block out the intense light of the host star, and lots of work will go into designing and developing such an instrument inside the observatory.

- In addition to the pioneering capabilities it will bring to the search for extraterrestrial life, HWO will be a full-service observatory for general astrophysics. It will study the earliest epochs of the history of the universe to understanding the life cycle and deaths of the most massive stars, which ultimately supply the elements that are needed to support life as we know it.

Julie Crooke, an optical systems engineer, is program executive for the Great Observatory Maturation Program (GOMAP.) Like many scientists and engineers involved with the effort, she has been active in many projects that led up to HWO, going back to 2007. (NASA)

So the plan is aggressive for sure.

“Our task is to work towards a mission that is not just ambitious and ground-breaking, but that is also achievable,” Domagal-Goldman said.

The keys to making that possible, he said, are matching NASA’s long heritage of successful and ever-more-complex technology (referred to during the development of the Webb Telescopes as “miracles” but now proven approaches) with a very early start on developing the needed technology that will be new. A primary goal of the maturation program Domagal-Goldman (and others) are leading is to reduce or eliminate the need for those miracles, while accomplishing previously impossible objectives.

“We believe that using our heritage and new technology, HWO should be able to not only characterize the chemistry in atmospheres of Earth-sized exoplanets, but do that enough times to get statistics on those worlds,” he said. “The goal is to determine how many of the potentially habitable worlds out there have oceans or signs of global biospheres.”

A 6-to-6.5 meter HWO mirror should be able to directly image small exoplanets in star systems out to 50 light-years away from Earth, explained John O’Meara, chief scientist of the Keck Observatory in Hawaii and co-chair of the science committee set up under GOMAP. That means the HWO scientists should have potentially hundreds of small, rocky exoplanets to select from and then stare at.

This animation shows how a planet can disappear in a star’s bright light and how a coronagraph, such as the one that will be used on Roman, can reveal it. ( NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/CI Lab)

If Earth were an exoplanet being observed from a distant planet, our Sun would outshine the light of our planet by 10 billion times. That would make it impossible to see, unless that sunlight was somehow suppressed.

The technology to achieve that kind of suppression is one of the great challenges of the HWO. NASA’s Roman Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2027, will have the first high performance coronagraph deployed in space and will be a test of sorts for HWO.

But the light suppression needed for the observatory is much greater than what the Roman will provide and so substantial technological progress will be necessary. The Roman telescope’s coronagraph will be able to block out the light of a star 100 million times brighter than its planet; the HWO’s coronagraph will need to cope with stars that are 10 billion times brighter.

The coronagraph will be connected to the light-collecting mirror and will require a near-absolute stability to pull small exoplanets out of the glare of their Suns. That level of stability is also something that will be new to HWO.

At a California Institute of Technology HWO technical workshop earlier this year, scientists and engineers met to discuss the starlight challenge and other technological hurdles. Regarding the coronagraph, the consensus among researchers and engineers was that they will have to push their technologies to the limit to achieve the necessary level of starlight suppression.

Said Dmitry Mawet, member of the HWO Technical Assessment Group (TAG): “As we get closer and closer to this required level of starlight suppression, the challenges become exponentially harder.”

One additional challenge will be suppressing stray light, which may require a cylindrical baffle around the HWO, similar to the one surrounding the Hubble telescope. That would protect its mirror from micrometeorites of the sort that have already struck the Webb Telescope. Every pit in the mirror from a meteorite strike causes stray light.

But if these challenges can be overcome in the years ahead, this is what Domagal-Goldman says can be achieved: “We’ll be able to image incredibly pale and distant blue dots, about as faint as anything imaged in the Hubble Deep Field.”

That is remarkable, given that the Hubble Deep Field image (below) contains nearly 10,000 galaxies, including some pretty faint ones. There are untold planets in the image, but none are visible.

There have been five Great Observatories launched since the program began in 1979 — the Spitzer Space Telescope, the Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory, the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb. Each of the five Great Observatories looks, or looked, out at the cosmos in different wavelengths, and together they and other telescopes have revolutionized how we understand the universe.

In recommending the HWO as a new Grand Observatory, the National Academy also called for the commissioning of two others, the Origins Space Telescope (to study star formation) and the Lynx X-Ray Observatory (which would study the origin of black holes and the evolving structure of galaxies.)

All fall under the pre-planning scope of the Great Observatory Maturation Program and are , like the HWO, not expected to launch for decades.

In approaching the enormous task of “maturing” the designs of these observatories, Domagal-Goldman said his group is looking to other very complex federal agency projects but also to undertakings such as planning an Olympic Games or building a new baseball stadium.

“NASA has never had a formal maturation program before, not in the same focused early sense,” he said. “We’re changing how we do things, and those changes will be a strategic investment that will decrease the risk of going over schedule and budget. That’s important because we need for this observatory and telescope to do things never done before.”

HWO science team co-chair O’Meara put it another, hand’s-on way. The GOMAP effort, he said, will “retire risks” before they can complicate later development, as happened with the Webb Telescope.

That early work will make sure that the technology proposed will support the science desired and will avoid a situation where “when we’re cutting metal, we don’t realize the technology pole is too tall” — i.e., that the fit isn’t right. “That’s costly trouble, because by then you have an army marching,” he said.

That GOMAP investment will be substantial. According to O’Meara of the HWO science definition team, the National Academy recommended that NASA spend many millions in its maturation program, a not insignificant part of the notional HWO budget. That budget, O’Meara said, would cover work for a five or six year period.

As of today, however, no money has actually been allocated by Congress for HWO and its maturation program. With next year’s federal budget unresolved, with spending caps looming and with a government shutdown next month as a possibility, O’Meara said it remains entirely unclear when funding for the maturation program will be passed and at what level. Funding so far has come out of the NASA astrophysics budget.

O’Meara has been talking with members of Congress about GOMAP and the HWO project and he says there is interest and concern.

“There are members of Congress who worry about the cost of the observatory and frankly would never support an observatory,” O’Meara said. “Then there are members who understand the great soft power that comes from these kinds of projects, which the world knows only the U.S. and its partners can build now. And then there are those who are fascinated by the science and see the search for life in the cosmos as very important and exciting for citizens.”

As the search for life beyond Earth proceeds around the globe, pulling in thousands of scientists working on an ever-growing number of approaches from a myriad of disciplines, there will be countless discoveries that move the field forward.

But we may well have to wait for results sent back by the Habitable Worlds Observatory to have anything close to a clear understanding of what life exists — or doesn’t exist — out there.