We all know that life has not been found so far on any planet beyond Earth — at least not yet. This lack of discovery of extraterrestrial life has long been used as a knock on the field of astrobiology and has sometimes been put forward as a measure of Earth’s uniqueness.

But the more recent explosion in exoplanet discoveries and the next-stage efforts to characterize their atmospheres and determine their habitability has led to rethinking about how to understand the lessons of life of Earth.

Because when seen from the perspective of scientists working to understand what might constitute an exoplanet that can sustain life, Earth is a frequent model but hardly a stationary or singular one. Rather, our 4.5 billion year history — and especially the almost four billion years when life is believed to have been present — tells many different stories.

For example, our atmosphere is now oxygen-rich, but for billions of years had very little of that compound most associated with complex life. And yet life existed.

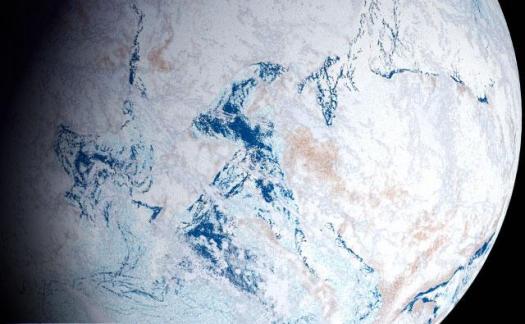

The same with temperature. Earth went through snowball or slushball periods when most of the planet’s surface was frozen over. Hardly a good candidate for life, and yet the planet remained habitable and inhabited.

And in its early days, Earth had a very weak magnetic field and was receiving only 70 to 80 percent as much energy from the sun as it does today. Yet it supported life.

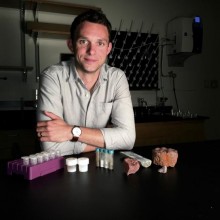

“It’s often said that there’s an N of one in terms of life detected in the universe,” that there is but one example, said Timothy Lyons, a biogeochemist and distinguished professor at University of California, Riverside.

“But when you look at the conditions on Earth over billion of years, it’s pretty clear that the planet had very different kinds of atmospheres and oceans, very different climate regimes, very different luminosity coming from the sun. Yet we know there was life under all those very different conditions.

“It’s one planet, but it’s silly to think of it as one planetary regime. Each of our past chapters is a potential exoplanet.”

Lyons is the principal investigator for one of the newer science teams selected to join the NASA Astrobiology Institute (NAI), an interdisciplinary group hat calls itself “Alternative Earths.”

Consisting of 23 scientists from 14 institutions, its self-described mission is to address and answer these questions: How has Earth remained persistently inhabited through most of its highly changeable history? How has the presence of very different kinds of lifeforms been manifested in the atmosphere, and simultaneously been captured in what would become the rock record? And how might this approach to early Earth help in the search for life beyond Earth?

“The idea that early Earth can help us understand other planets and moons, especially in our solar system, is certainly not new,” Lyons said. “Scientists have studied possible Mars analogues and extreme life for years. But we’re taking it to the next level with exoplanets, and pushing hard on the many ways that conditions on early Earth can help us study exoplanet atmospheres and habitability.”

The importance of this work was apparent at a recent workshop on biosignatures held by NASA’s initiative, the Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS.) As Earth scientists, Lyons and his group are expert at finding proxy records in ancient rocks that hold information important to exoplanet scientists (among others) want to know.

Those proxy fingerprints occur as elemental, molecular, and isotopic properties preserved in rocks that correspond to ancient characteristics in the ocean or atmosphere that can no longer be observed directly.

“We can’t measure the pH in ancient oceans, and we can’t measure the composition of ancient atmospheres,” Lyons said. “So what we have to do is go to the chemistry of ocean and land deposits formed at the same time and look for the chemical fingerprints locked away and preserved.”

At the exoplanet biosignatures workshop, Lyons was struck by how eager exoplanet modelers were to learn about the proxy chemicals they could profitably put in their models for clues about how distant planet atmospheres might form and behave. It’s clear that no single element or compound will be a silver bullet for understanding whether there’s life on an exoplanet, but a variety of proxy results together can begin to tell an important story.

“We told them about the range of things they should be modeling and, wow, they were interested. I was thinking at the time that ‘you guys really need us — and vice versa.'”

Some of the researchers most intrigued by potentially new geochemical proxies from the University of Washington’s Virtual Planetary Laboratory, They’ve been a pioneer in modeling how different atmospheric, geological, stellar and other factors characterize particular kinds of planets and solar systems and their possibilities for life.

In keeping with the growing connection between exoplanet and Earth science, Lyons just brought one of the VPL top modellers, Edward Schwieterman, to UC Riverside for a postdoc as part of the Alternative Earths project.

Among his initial projects will take the new data being generated by the Alternative Earths team about the atmosphere and oceans of early Earth, and model what would happen on a planet with that kind of atmosphere if it was orbiting a very different type of star from our own.

“It’s a direct use of early Earth research on exoplanet studies, and is exactly the kind of work we plan to do be doing,” Lyons said. “Eddie is the perfect bridge between the lessons learned from early Earth and their implications for exoplanets.”

Lyons, along with colleagues Christopher Reinhard of Georgia Tech and Noah Planavsky of Yale and other members of their Alternative Earths team, are especially focused on an effort to understand Earth’s atmosphere—as tracked in the rock record—over the eons and especially the levels of oxygen present.

The concentration of oxygen in the atmosphere is now about about 21 percent and, by some estimates, reached as high as 35 percent within the past 500 million years.

In comparison, early Earth had but trace amounts of oxygen for two billion years before what is called the Great Oxidation Event—when marine O2-producing photosynthesis outpaced reactions that consumed O2 and allowed for the beginnings of its permanent accumulation in the atmosphere. Estimated to have occurred 2.4 billion years ago, it began (or was part of) an oxidizing process that led to ever more complex life forms over the following one to two billion years.

There is a spirited scientific debate underway now about whether that “Great Oxidation Event” triggered permanently high levels of oxygen in the atmosphere and the oceans, or whether it began an up and down process through which the presence of oxygen was quite unstable and still well below current levels until relatively recent times.

Lyons and Reinhard are of the “boring billion” school, arguing that oxygen levels did not head continuously upwards after the Oxidation Event, but rather stayed relatively stable and still very low for most of a billion and half years after the Great Oxidation Event and continued to challenge O2-requiring life—for almost a third of Earth history.

This would be primarily an Earth science issue if not for the fact that oxygen — on its own and in conjunction with other compounds — is among the most prominent and promising biosignatures that exoplanet scientists are looking for.

In fact, not that long ago, it was widely accepted that a discovery of oxygen and/or ozone in the atmosphere of a planet pretty much proved, or at least strongly suggested, the presence of some sort of biology on the planet below. That view has been modified of late by the identification of ways that free oxygen can be formed abiotically (without the presence of photosynthesis and life), potentially producing false positives for potential life.

While the field is a long way from an active search for direct, in situ fingerprints of life on exoplanets light years away, oxygen and its relationship with other atmospheric gases remains a lodestar in thinking about what biosignatures to search for. The technology is already in place for characterizing the compositions of very distant atmospheres.

And this is where, for Lyons, Reinhard and others, things get both interesting and complicated.

For more than a billion years before the Great Oxidation Event Earth demonstrably supported life. It consisted mostly of anaerobic microbes that did just fine without oxygen, but in many cases needed and produced methane, an organic compound with one carbon atom and four hydrogens.

So if an exoplanet scientist from a distant world were to search for life on Earth during that period via the detection of oxygen only, they would entirely miss the presence of an already long history of life. Searching for a potentially large-scale presence of methane might have been more productive, though that is a source of rigorous debate as well.

Because both oxygen and methane can be formed without life, a current gold standard for detecting future biosignatures on exoplanets is the presence of the two together. As a result of the way the two interact, they would remain in an atmosphere together only if both were being replenished on a substantial, on-going scale. And as far as is now understood, the only way to do that is through biology.

Yet as described by Reinhard, the most current research suggest that oxygen and methane were probably never in the Earth’s atmosphere together at levels that would be detectable from afar. There is some evidence that Earth’s atmosphere held a lot of methane in its early times, and there has been a lot of oxygen for the past 600 million years or so, but as one grew in concentration the other declined — and during the “boring billion” both were likely low.

“So we have a complicated situation here where using the best exoplanet biosignatures we have now, intelligent beings looking at Earth over the past 4.5 billion years would not find a convincing signature of life for most, or maybe all, of that time if they relied only on co-occurrence of oxygen and methane,” Reinhard said. Yet there has been life for at least 3.7 billion years, and those beings studying Earth would have come up with a very false negative.

Lyons insists this is should not be a source of pessimism in the search for life on exoplanets, instead it is a “call to arms for new and more creative possibilities rather than the lowest hanging fruit.” It’s a challenge “to help us sharpen our thinking in a search that was never going to be easy.”

And the best test bed available for coming up with different answers, he said, may very well be the many different Earths that have come and gone on our planet.