(ESO/M. Kornmesser)

The detection of potentially habitable exoplanets is not the big news it once was — there have been so many identified already that the novelty has faded a bit. But that hardly means surprising and potentially breakthrough discoveries aren’t being made. They are, and one of them was just announced Monday.

This is how the European Southern Observatory, which hosts the telescope used to make the discoveries, introduced them:

Astronomers using the TRAPPIST telescope at ESO’s La Silla Observatory have discovered three planets orbiting an ultra-cool dwarf star just 40 light-years from Earth. These worlds have sizes and temperatures similar to those of Venus and Earth and are the best targets found so far for the search for life outside the Solar System. They are the first planets ever discovered around such a tiny and dim star.

A team of astronomers led by Michaël Gillon, of the Institut d’Astrophysique et Géophysique at the University of Liège in Belgium, have used the Belgian TRAPPIST telescope to observe the star, now known as TRAPPIST-1. They found that this dim and cool star faded slightly at regular intervals, indicating that several objects were passing between the star and the Earth. Detailed analysis showed that three planets with similar sizes to the Earth were present.

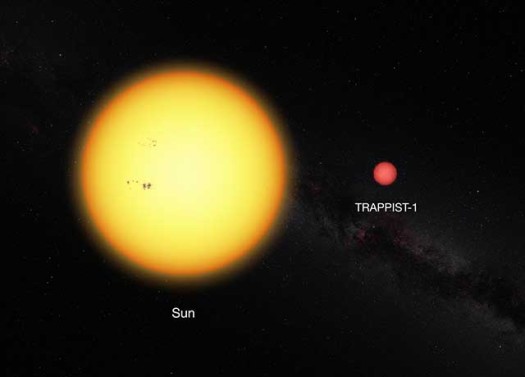

The discovery has much going for it — the relative closeness of the star system, the rocky nature of the planets, that they might be in habitable zones. But of special importance is that the host star is so physically small and puts out a sufficiently small amount of radiation that the planets — which orbit the star in only days — could potentially be habitable even though they’re so close. The luminosity (or power) of Trappist-1 is but 0.05 percent of what’s put out by our sun.

This is a very different kind of sun-and-exoplanet system than has generally been studied. The broad quest for an Earth-sized planet in a habitable zone has focused on stars of the size and power of our sun. But this one is 8 percent the mass of our sun — not that much larger than Jupiter.

“This really is a paradigm shift with regards to the planet population and the path towards finding life in the universe,” study co-author Emmanuël Jehin, an astronomer at the University of Liège, said in a statement. “So far, the existence of such ‘red worlds’ orbiting ultra-cool dwarf stars was purely theoretical, but now we have not just one lonely planet around such a faint red star but a complete system of three planets!”

The TRAPPIST-1 star is very faint and was identified because a Belgian team built a telescope especially to look for stars, and exoplanets, like the ones they found. TRAPPIST (TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope) is tiny by today’s standards, but collects light at infrared wavelengths and that makes it well designed for the task.

The observations began only in September, 2015, and targeted a dwarf star well known to astronomers. TRAPPIST spends much of its time monitoring the light from around 60 of the nearest ultracool dwarf stars and brown dwarfs (“stars” which are not quite massive enough to initiate sustained nuclear fusion in their cores), looking for evidence of planetary transits.

Because the star and planets are so relatively close, they offer an unusual opportunity to potentially characterize the atmospheres of the planets and determine what molecules are in the air. These measurements are essential to learning whether a planet is indeed habitable (or even inhabited.)

Co-author Julien de Wit, a postdoc in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, said scientists will soon be able to study the planets’ atmospheric compositions quite soon.

“These planets are so close, and their star so small, we can study their atmosphere and composition, and further down the road, which is within our generation, assess if they are actually inhabited,” de Wit said. “All of these things are achievable, and within reach now. This is a jackpot for the field.”

Rory Barnes, a specialist in dwarf stars and their exoplanets at the University of Washington, agreed that the TRAPPIST-1 discovery was both intriguing today and inviting of a lot more future study. Indeed, he said that efforts to characterize exoplanet atmospheres will most likely focus for the next decade on the smaller stars in our galactic neighborhood — the ubiquitous M dwarfs.

“It’s just easier to find exoplanets around smaller stars because they block out a great percentage of the star’s light when they transit,” he said. “And with small stars, the planets are usually closer in, which also makes them easier to find.”

But there are also significant barriers to habitability in the TRAPPIST-1 system. Because the planets are so close to their host star — the first has an orbit of 1.5 days, the second an orbit of 2.4 days and the third an ill-defined orbit of between 4.5 and 73 days — that means they are tidally-locked, as is our moon. Not long ago, exoplanet scientists doubted that a planet that doesn’t rotate can be truly habitable since the extremes of hot and cold would be too great. That view has changed with creation of models that suggest tidal locking is not necessarily fatal for habitability, but it most likely does make it more difficult to achieve.

A larger potential barriers is that the dwarf star once was quite different. Jonathan Fortney, a University of California at Santa Clara specialist in dwarf stars and brown dwarfs (objects which are too large to be called planets and too small to be stars), focused on that stellar history:

“One thing to keep in mind is that this star was much much brighter in the past,” he said in an email. “M stars (like TRAPPIST-1) are hottest when they are young and take a long time to cool off and settle down. Their energy comes from contraction at first. A star like this takes 1 billion years to even settle onto the main sequence (where it starts burning hydrogen).”

Barnes also focused on the stellar evolution, which he said is always complex and pertinent when talking about dwarf stars and exoplanets. A small dwarf star like TRAPPIST-1 — which the authors estimate is 500 million years old — would have spent a much longer time as a much hotter protostar, sending out intense heat from its formation process before it achieved fusion. That means a planet in the star’s habitable zone now may well have been baked like Venus eons ago, Barnes said, and there is no known way to become habitable after that.

So the relatively benign conditions around TRAPPIST-1 now in terms of radiation and heat clearly have not always been present.

The study authors said — and other scientists agree — that the most likely planet in the system to be actually habitable is the one furthest out. But the orbit of that third planet has not been well defined, as seen in the estimate that it orbits its star within somewhere between 4.5 and 73 days.

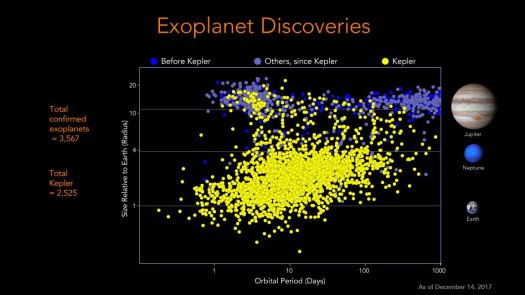

As it turns out, the follow-on Kepler mission (K2) will be observing in the area that includes TRAPPIST-1 from this coming December through March 2017.

Kepler Mission Scientist Natalie Batalha said that she hoped the team put in a proposal to observe TRAPPIST-1. If they did, she said, the proposal will be peer reviewed this month and could be among those selected. Assuming the telescope is in good working order and operations continue to be funded come December, K2 observations could better define that third planet’s orbit.

But whatever happens with K2, TRAPPIST-1 is now an astronomical “star” and will no doubt be getting scientific attention of all kinds.