An earlier version of this article was accidently published last week before it was completed. This is the finished version, with information from this week’s AAS annual conference.

Let’s face it: the field of exoplanets has a significant deficit when it comes to producing drop-dead beautiful pictures.

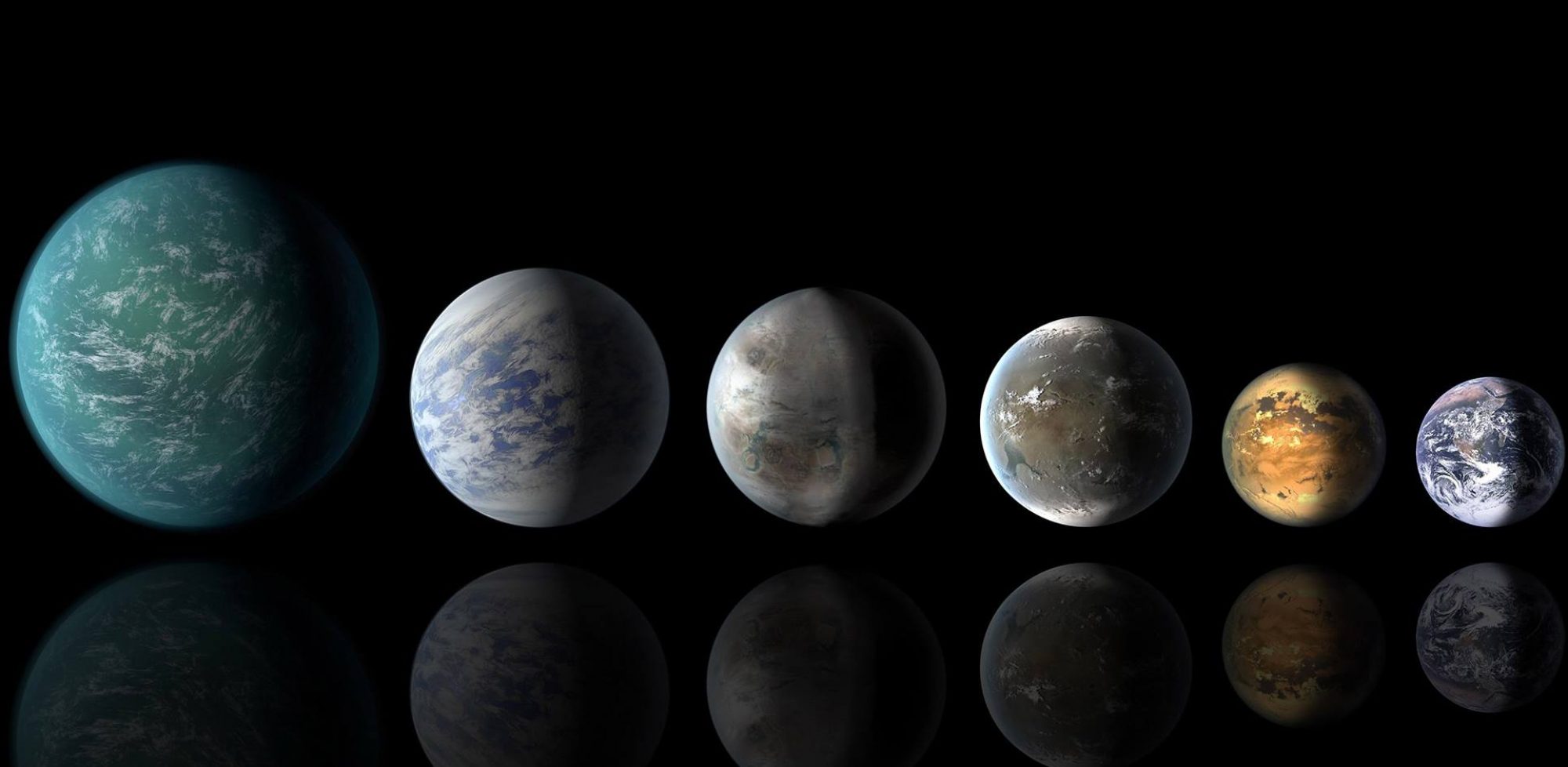

We all know why. Exoplanets are just too small to directly image, other than as a miniscule fraction of a pixel, or perhaps some day as a full pixel. That leaves it up to artists, modelers and the travel poster-makers of the Jet Propulsion Lab to help the public to visualize what exoplanets might be like. Given the dramatic successes of the Hubble Space Telescope in imaging distant galaxies, and of telescopes like those on the Cassini mission to Saturn and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, this is no small competitive disadvantage. And this explains why the first picture of this column has nothing to do with exoplanets (though billions of them are no doubt hidden in the image somewhere.)

The problem is all too apparent in these two images of Pluto — one taken by the Hubble and the other by New Horizons telescope as the satellite zipped by.

Pluto is about 4.7 billion miles away. The nearest star, and as a result the nearest possible planet, is 25 trillion miles away. Putting aside for a minute the very difficult problem of blocking out the overwhelming luminosity of a star being cross by the orbiting planet you want to image, you still have an enormous challenge in terms of resolving an image from that far away.

While current detection methods have been successful in confirming more than 2,000 exoplanets in the past 20 years (with another 2,000-plus candidates awaiting confirmation or rejection), they have been extremely limited in terms of actually producing images of those planetary fireflies in very distant headlights. And absent direct images — or more precisely, light from those planets — the amount of information gleaned about the chemical makeup of their atmospheres as been limited, too.

But despite the enormous difficulties, astronomers and astrophysicist are making some progress in their quest to do what was considered impossible not that long ago, and directly image exoplanets.

In fact, that direct imaging — capturing light coming directly from the sources — is pretty uniformly embraced as the essential key to understanding the compositions and dynamics of exoplanets. That direct light may not produce a picture of even a very fuzzy exoplanet for a very long time to come, but it will definitely provide spectra that scientists can read to learn what molecules are present in the atmospheres, what might be on the surfaces and as a result if there might be signs of life.

There has been lots of technical and scientific debate about how to capture that light, as well as debate about how to convince Congress and NASA to fund the search. What’s more, the exoplanet community has a history of fractious internal debate and competition that has at times undermined its goals and efforts, and that has been another hotly discussed subject. (The image of a circular firing squad used to be a pretty common one for the community.)

But a seemingly much more orderly strategy has been developed in recently years and was on display at the just-completed American Astronomical Society annual meeting in Florida. The most significant breaking news was probably that NASA has gotten additional funds to support a major exoplanet direct imaging mission in the 2020s, the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), and that the agency is moving ahead with a competition between four even bigger exoplanet or astrophysical missions for the 2030s. The director of NASA Astrophysics, Paul Hertz, made the formal announcements during the conference, when he called for the formation of four Science and Technology Definition Teams to assess in great detail the potentials and plausibilities of the four possibilities.

Putting it into a broader perspective, astronomer Natalie Batalha, science lead for the Kepler Space Telescope, told a conference session on next-generation direct imaging that “with modern technology, we don’t have the capability to image a solar system analog.” But, she said, “that’s where we want to go.”

And the road to discovering exoplanets that might actually sustain life may well require a space-based telescope in the range of eight to twelve meters in radius, she and others are convinced. Considering that a very big challenge faced by the engineers of the James Webb Space Telescope (scheduled to launch in 2018) was how to send a 6.5 meter-wide mirror into space, the challenges (and the costs) for a substantially larger space telescope will be enormous.

We will come back in following post to some of these plans for exoplanet missions in the decades ahead, but first let’s look at a sample of the related work done in recent years and what might become possible before the 2020s. And since direct imaging is all about “seeing” a planet — rather than inferring its existence through dips in starlight when an exoplanet transits, or the wobble of a sun caused by the presence of an orbiting ball of rock (or gas) — showing some of the images produced so far seems appropriate. They may not be breath-taking aesthetically, but they are remarkable.

There is some debate and controversy over which planets were the first to be directly imaged. But all agree that a major breakthrough came in 2008 with the imaging of the HR8799 system via ground-based observations.

First, three Jupiter-plus gas giants were identified using the powerful Keck and Gemini North infrared telescopes on Mauna Kea in Hawaii by a team led by Christian Marois of the National Research Council of Canada’s Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics. That detection was followed several years later the discovery of a fourth planet and then by the release of the surprising image above, produced with the quite small (4.9 foot) Hale telescope at the Palomar Observatory outside of San Diego.

As is the case for all planets directly imaged, the “pictures” were not taken as we would with our own cameras, but rather represent images produced with information that is crunched in a variety of necessary technical ways before their release. Nonetheless, they are images in a way similar the iconic Hubble images that also need a number of translating steps to come alive.

Because light from the host star has to be blocked out for direct imaging to work, the technique now identifies only planets with very long orbits. In the case of HR8799, the planets orbit respectively at roughly 24, 38 and 68 times the distance between our Earth and sun. Jupiter orbits at about 5 times the Earth-sun distance.

In the same month as the HR8799 announcement, another milestone was made public with the detection of a planet orbiting the star Formalhaut. That, too, was done via direct imagining, this time with the Hubble Space Telescope.

Signs of the planet were first detected in 2004 and 2006 by a group headed by Paul Kalas at the University of California, Berkeley, and they made the announcement in 2008. The discovery was confirmed several years later and tantalizing planetary dynamics began to emerge from the images (all in false color.) For instance, the planet appears to be on a path to cross a vast belt of debris around the star roughly 20 years from now. If the planet’s orbit lies in the same plane with the belt, icy and rocky debris could crash into the planet’s atmosphere and cause interesting damage.

The region around Fomalhaut’s location is black because astronomers used a coronagraph to block out the star’s bright glare so that the dim planet could be seen. This is essential since Fomalhaut b is 1 billion times fainter than its star. The radial streaks are scattered starlight. Like all the planets detected so far using some form of direct imaging, Fomalhaut b if far from its host star and completes an orbit every 872 years.

Adaptive optics of the Gemini Planet Imager, at the Gemini South Observatory in Chile, has been successful in imaging exoplanets as well. The GPI grew out of a proposal by the Center for Adaptive Optics, now run by the University of California system, to inspire and see developed innovative optical technology. Some of the same breakthroughs now used in treating human eyes found their place in exoplanet astronomy.

The Imager, which began operation in 2014, was specifically created to discern and evaluate dim, newer planets orbiting bright stars using a different kind of direct imaging. It is adept at detecting young planets, for instance, because they still retain heat from their formation, remain luminous and visible. Using the GPI to study the area around the y0ung (20-million-year-old) star 51 Eridiani, the team made their first exoplanet discovery in 2014.

By studying its thermal emissions, the team gained insights into the planet’s atmospheric composition and found that — much like Jupiter’s — it is dominated by methane. To date, methane signatures have been weak or absent in directly imaged exoplanets.

James Graham, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley, is the project leader for a three-year GPI survey of 600 stars to find young gas giant planets, Jupiter-size and above.

“The key motivation for the experiment is that if you can detect heat from the planet, if you can directly image it, then by using basic science you can learn about formation processes for these planets.” So by imaging the planets using these very sophisticated optical advances, scientists go well beyond detecting exoplanets to potentially unraveling deep mysteries (even if we still won’t know what the planets “look like” from an image-of-the-day perspective.

The GPI has also detected a second exoplanet, shown here at different stages of its orbit:

A next big step in direct imaging of exoplanets will come with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope in 2018. While not initially designed to study exoplanets — in fact, exoplanets were just first getting discovered when the telescope was under early development — it does now include a coronagraph which will substantially increase its usefulness in imaging exoplanets.

As explained by Joel Green, a project scientist for the Webb at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, the new observatory will be able to capture light — in the form of infrared radiation– that will be coming from more distant and much colder environments than what Hubble can probe.

“It’s sensitive to dimmer things, smaller planets that are more earth-sized. And because it can see fainter objects, it will be more help in understanding the demographics of exoplanets. It uses the infrared region of the spectrum, and so it can look better into the cloud levels of the planets than any telescope so far and see deeper.”

These capabilities and more are going to be a boon to exoplanet researchers and will no doubt advance the direct imaging effort and potentially change basic understandings about exoplanets. But it is not expected produce gorgeous or bizarre exoplanet pictures for the public, as Hubble did for galaxies and nebulae. Indeed, unlike the Hubble — which sees primarily in visible light — Webb sees in what Green said is, in effect, night vision. And so researchers are still working on how they will produce credible images using the information from Webb’s infrared cameras and translating them via a color scheme into pictures for scientists and the public.

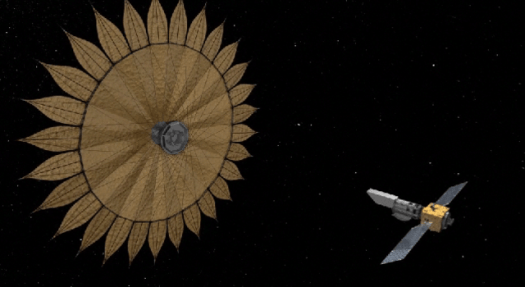

Another compelling exoplanet-imaging technology under study by NASA is the starshade, or external occulter, a metal disk in the shape of a sunflower that might some day be used to block out light from host stars in order to get a look at faraway orbiting planets. MIT’s Sara Seager led a NASA study team that reported back on the starshade last year in a report that concluded it was technologically possible to build and launch, and would be scientifically most useful. If approved, the starshade — potentially 100 feet across — could be used with the WFIRST telescope in the 2020s. The two components would fly far separately, as much as 35,000 miles away from each other, and together could produce breakthrough exoplanet direct images.

Here is a link to an animation of the starshade being deployed: http://planetquest.jpl.nasa.gov/video/15

The answer, then, to the question posed in the title to this post — “How Will We Know What Exoplanets Look Like, and When?”– is complex, evolving and involves a science-based definition of what “looking like” means. It would be wonderful to have images of exoplanets that show cloud formations, dust and maybe some surface features, but “direct imaging” is really about something different. It’s about getting light from exoplanets that can tell scientists about the make-up of those exoplanets and their atmospheres, and ultimately that’s a lot more significant than any stunning or eerie picture.

And with that difference between beauty and science in mind, this last image is one of the more striking ones I’ve seen in some time.

It was taken at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile last year, during a night of stargazing. Although the observatory is in the Atacama Desert, enough moisture was present in the atmosphere to create this lovely moon-glow.

But working in the observatory that night was Carnegie’s pioneer planet hunter Paul Butler, who uses the radial velocity method to detect exoplanets. But to do that he needs to capture light from those distant systems. So the night — despite the beautiful moon-glow — was scientifically useless.