The central and ever-surprising story of water on ancient Mars took a new turn recently when NASA announced that the Perseverance rover had found the fossil remains of a once-powerful river in Jezero Crater.

From the nature and patterns of the riverbed turned to stone, to the ways that grains of sand and rocks been moved, textured and deposited and to the features of the surrounding landscape, the rover science team came go a speedy conclusion: This was a Mars river of substance. It carried substantial tonnages of sediment and rocks of some size, and laid down deep layers of sediment.

“We’re seeing what looks like the result of sudden, abrupt, high-energy inflow of water, carrying a lot of debris,” said Libby Ives, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “This was no tiny stream; it was a pretty big channel.”

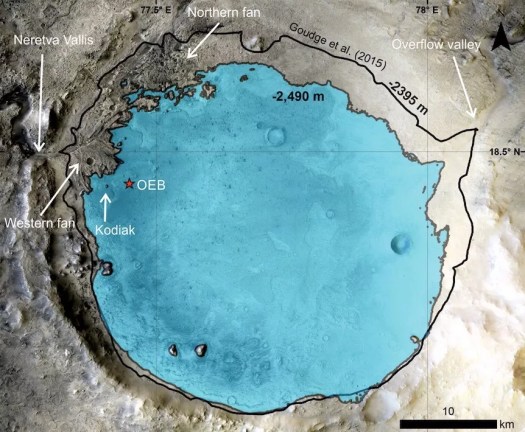

But there’s more. The river was not only powerful it was also deep — especially where it apparently emptied into a large lake. This was a very different kind of water environment at ancient Jezero than what the previous NASA rover, Curiosity, found in Gale Crater.

“At Gale, you could wade through the water we found evidence for,” said Kathryn Stack Morgan, deputy science lead for Perseverance and formerly a member of the Curiosity science team.

“Here, we’re talking about scuba diving. This was really surprisingly deep.”

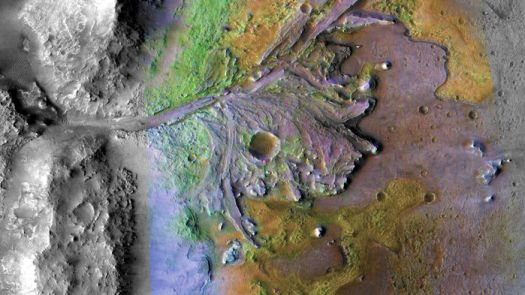

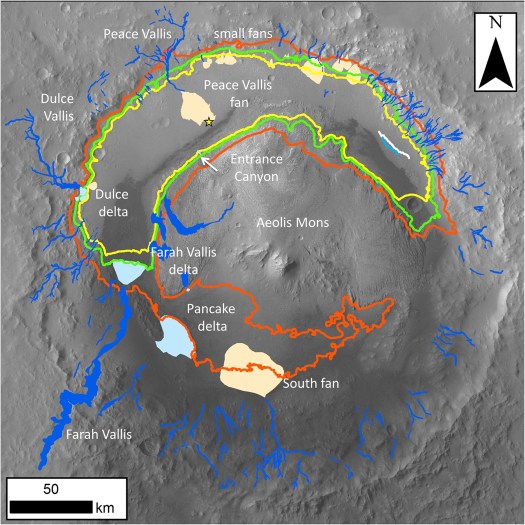

Mars scientists have long observed via orbiting satellites what they concluded were deep rivers on Mars. The area around the recently discovered riverbed actually had features that were interpreted from orbit to form a likely riverbed — part of a network of waterways that flowed into Jezero.

But Stack said that having the rover directly on the ancient riverbed, to have it observing and analyzing a substantial river that once existed, is a very different experience.

“In many ways it’s not a surprise that we’d find deposits like this,” she said. “After all, we know there had to be a lot of water in Jezero because the crater at least once filled and spilled out the other side.”

“But coming up to it with the rover makes it real in a different way, and we now are forced to explain some pretty amazing things. For instance, we’re right in front of an outcrop of 20 meters (66 feet) that we think had to have been deposited in as much water as that.”

“So we’re actually seeing evidence of water not just in land forms and channels and topography, but in the environments left behind and recorded in the rock record. We have to grapple with that.”

This, then, seems like a good moment to step back and see where the longtime NASA mantra of “Follow the Water” on Mars has taken us. After all, following the water — the world’s universal solvent — is not only a path forward to understand the planet and its history, but also is the path NASA took in its search for signs of life on Mars.

Mars is now a parched, frigid place, with an average global temperatures of -81 degrees F. It’s hard to imagine that sections of the planet were once potentially habitable and with liquid water, as NASA scientists have now concluded.

The foundation of that conclusion is based in the discoveries made over recent decades — all the remains of ancient lakes, deltas and rivers, of signs of subsurface groundwater, of minerals only formed in liquid water. There is a broad consensus among Mars scientists that the planet was once considerable wetter and warmer than it is today.

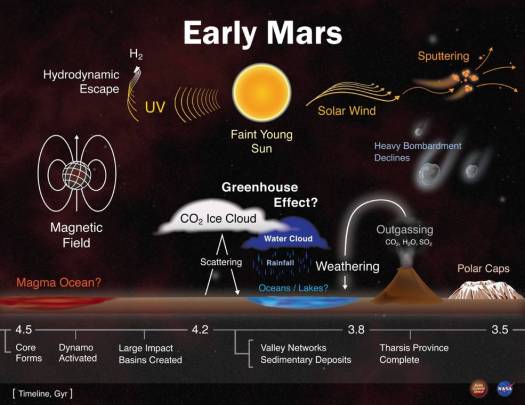

But how wet and warm early Mars may have been — before it lost its atmosphere some 3.5 to 4 billion years ago — remains a subject of great debate. While the Martian topography that has been explored by rovers and orbiters tells of a time with lots of water, the climate models tell of a much drier time.

Here’s the problem: Mars never had a magnetic field as strong as ours, and as a result never had an atmosphere as thick as ours. So the planet has been subject to eons to the assault of solar and cosmic radiation as well as the solar wind, and together they destroyed much of the Martian atmosphere long ago. It is hard to imagine the presence of liquid water without some kind of warming and protective atmosphere, climate modelers have long argued.

Adding to the problem of a thin or absent atmosphere is that early Mars — when the surface seemingly had a not insignificant amount of liquid water — also existed in a colder solar system. The Sun was immature then, not as powerful as it is now, and so there was less heat coming off it, an estimated 70 percent of what is available now. As a result, less heat was arriving at Mars (substantially further from the Sun than Earth) in that early period to warm the planets.

And yet, evidence of early water features on Mars are prevalent.

Not surprisingly, the nature of those signatures of a watery Mars changes with the landscapes — as on Earth.

For instance, the decade-long exploration of Gale Crater by the Curiosity rover has found a setting that may never had deep reservoirs of water, but it clearly had water over a long period of time.

As Stack explained, the travels and samplings accomplished by Curiosity have provided a remarkable picture of what appears to have happened in the crater. The oldest deposits telling of a watery past are in a region called Yellowknife Bay, and it was a lake setting.

Early in the Curiosity mission, the team extensively investigated a lowland they named Yellowknife Bay. They concluded that it not only once held water that flow in from streams spread into alluvial fans coming off the crater walls, but that the water was almost certainly potable for living creatures. As a result, the area was determined to have once been habitable.

As Curiosity made its way alongside Mount Sharp and got in position for its years-long climb, the rover came across other evidence of standing water in the Murray formation, evidence in the form of several hundred meters of lake margin sediment. And the rover came across the water at different elevations, suggesting a its presence over time.

“At Gale, you have to think of water being present for millions of years, of a long record of repeated water features,” Stack said. “That means there was a stability in the environment and that if life was ever present it could have taken hold and evolved.”

It’s too early to make any similar claims about Jezero Crater. But as Stack and Ives described Jezero and its once fast-flowing river, it definitely existed in a quite different environment from Gale.

“From what we’ve learned so far, Jezero was likely watery for a much shorter period of time than Gale,” Stack said. “But there definitely was a lot of water there.”

How does the Perseverance team know that? Among other evidence, there are clear geological signs that at one point at least, the whole of Jezero Crater — which is 28 miles in diameter — filled with water to the point that it spilled out onto the surrounding land.

Ives said the team could tell their Jezero find was a fast-moving river because of the relatively coarseness of the sand grains found and because of substantial cobbles (rocks larger than pebbles and smaller than boulders) that had clearly been carried forward by the river.

If the river was as powerful as it seems, then the inevitable question is where did all that water come from, and what might have set it rushing onward?

The more shallow alluvial fans and lakes of Gale Crater were determined to have been filled by filled rivers beyond the crater rim fed perhaps by rainfall and ice melt during warm periods. But that combination would not create the kind of flow seen at Jezero.

Ives said the team studying the Jezero river explored possibilities including a volcanic eruption that would have warmed subsurface ice.

But the current thinking, she said, is that it may well have been the result of a glacial outburst flood — an event similar to what periodically happens especially in Iceland, but also in other northern locations. This kind of large release happens when meltwater at the base of a glacier builds to the point where it floods out.

“This is the level of drama we’re talking about here,” she said. “It would have been a watershed altering event and not a Mars shattering one.”

Finding an Earth-like event to explain a river feature on Mars is not at all unusual. Indeed, Ives said the features of Martian rivers appear to be quite similar to those on Earth, even though Mars has far less gravity and always had a much thinner atmosphere.

The biggest differences involve where the water originated. On Earth the water is produced by a long-standing water cycle that feeds rivers and lakes on Earth.

While there is some reason to think regular precipitation did occur on early Mars — and the NASA lander Phoenix even photographed some snow falling on the Martian surface — the cycles were far more limited on Mars and river forming was more a result of large dramatic events that free the ices in the surface.

While the Perseverance mission to Jezero is often presented in terms of its search for signs of early life — and the sample-collecting role it will play in the larger Mars sample return mission — much of its science involves geology, geochemistry and increasing our understanding of physical Mars.

Some of that most interesting work can get overshadowed by astrobiology and the search for signs of ancient life, which is of paramount interest to many people. But the geological findings not only provide the big picture needed to search for signs of ancient life, but also they are often just fascinating.

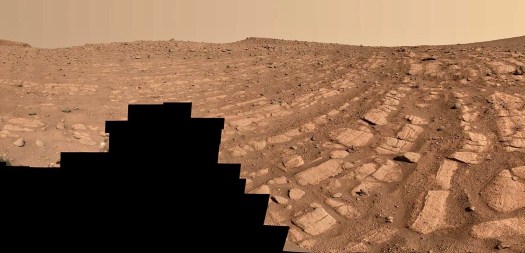

The two new images from Jezero above, of Skrinkle Haven and Pinestand, are a good example of this.

As described by Ives, the Skrinkle Haven formation has curved layers arranged in rows that team members say are possibly remnants of a river’s bank that shifted and turned to stone, or they may be remnants of sandbars in the river. She said that a nearby but seemingly stand-alone hill called Pinestand is also believed to be made up of sedimentary layers stacked on top of one another by a deep, fast-moving river. In this case, the layers reach up more than 60 feet.

To my surprise, Ives said that if the rover could climb to the broad top of Pinestand, it would most likely find the same kind of curved and in rows formations as nearby Skrinkle Haven. That’s because Pinestand was likely created by a related river channel. And then, via inverted topography, what used to be river valleys become ridges.

This occurred because the river channel remains, as well as delta deposits, are more resistant to the Martian winds and radiation and general weathering that carves away any softer material.

A similar process can unfold in a river channel itself. Sediment turned into rock in the middle of what was the river can be substantially elevated in comparison with what had been the banks and surrounds of the river. These formations — found on Earth as well as Mars — are called inverted channels.

As Ives explained, a lot of the sediment in the Jezero fossil river is coarse, which is generally consistent with a relatively fast flowing river. There are also abrupt switches in textures in the sands and cobbles, indicating quick changes in the flow of water.

These findings and more are being used to determine what kind of river the Perseverance team is studying. It is a distributary river, receiving water from a massive inflow channel entering Jezero and carrying it to a crater lake. The team expected a “meandering” river, rather like the lower Mississippi, but instead seem to have found a “braided” river like the Platte or Missouri.

The evolving story of water on Mars is written through geology and geochemistry but also through climate modelling and investigating the early Mars atmosphere. The two are wedded, but it has not always been a smooth marriage.

We have already brought up the stubborn reality that warming up early Mars enough to create fossil lakes and riverbeds is a huge problem because of the distance from the Sun to Mars and also because or the “faint young Sun” problem. During the period 3.5 to 4 billion years ago, the Sun was sending out only 70 percent as much heat as it does now.

Robin Wordsworth, a planetary scientist at Harvard University, has long been involved in the effort to square this circle, conditions on early Mars would have been akin to Antarctica in winter.

Given these conditions, Mars clearly needed chemicals in its atmosphere that created some kind of strong greenhouse effect. But the search for the molecules (or for frequent large-scale events such as volcanoes or small asteroid strikes) that can explain the undeniably watery history of Mars remains a work in progress. There was not enough carbon dioxide, for instance, to have played a central role.

While he still has graduate students exploring greenhouse gas chemicals that could have been in the early Martian atmosphere, Wordsworth said an evolving consensus invokes a different approach to the question.

The warming periods, he said, were likely relatively short and episodic. “I think the best explanation is that you have pulses of warming of hundreds or thousand or millions of years.”

Wordsworth said that a viable, though not a consensus, explanation of how this would occur involves the release of hydrogen by erupting volcanoes. The hydrogen would then react with the limited oxygen, methane and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to raise global temperatures to the point needed to explain Martian river valleys and the lakes and rivers of Gale and Jezero (and many more.)

But he said it’s essential to keep in mind that Mars — even when it was young — was always a very dry planet. He said estimates for the sum total of water on Mars in its early days was about 30 meters spread globally. A comparable figure of the water layer that would be created on Earth if similarly calculated would be over two miles globally. And Earth is not considered a particularly wet planet.

Wordsworth, and many other climate modelers, think that a generally cold and dry Mars, with relatively short periods of some warmth, can explain the geological evidence that has been collected about lakes and rivers.

He also thinks that the generally cold and dry scenario would not at all rule out the emergence of life. In fact, he said, some research has concluded that periods of wet and then dry conditions may well be necessary to form the organics and other molecules needed for life.

“The key here is learning about the Martian organic cycle — how might complex organics be produced?” Answers, he believes, may well be tucked away in the Martian subsurface.

Wordsworth is not a member of the Perseverance team, nor has he been on the Curiosity team. He volunteers that there are others who argue for a wetter and warmer early Mars, including those who find evidence for an ancient large ocean on the much shallower northern hemisphere of the planet.

But Wordsworth is well respected in the field and was recommended by Ashwin Vasavada, the current project scientist for the Curiosity mission. And Wordsworth is comfortable with saying that the warming of early Mars remains a very open question.

While NASA and other researchers have made tremendous progress over the decades in piecing together the Mars water story, a broad consensus exists that an essential next step is to bring some samples of Mars back to Earth.

In 2006, the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group identified 55 important investigations related to Mars exploration. In 2008, they concluded that about half of the investigations “could be addressed to one degree or another by MSR (Mars Sample return)”, making the effort “the single mission that would make the most progress towards the entire list” of investigations. The report also concluded that a significant fraction of the investigations could not be meaningfully advanced without returned samples.

That was some years ago and, if anything, the necessity of the sample return project is seen as greater now by the Mars science community.

One crucial goal is to finally establish exact ages for when Mars rocks were formed. This “geochronology” will help scientists understand precisely when Mars had liquid water flowing, spreading and seeping below the surface in a specific place . Clearly, this knowledge will allow scientists to understand Mars in an entirely new way.

The returned samples would also be studied for chemical clues to the physical environments of ancient Mars and yes, they will also be studied for signatures of ancient life or of insights into whether Mars had the complex organics that could lead to the emergence of life.

The Perseverance rover is now collecting powered samples from Jezero and caching them for a future recovery. Together with the European Space Agency, NASA is developing architectures for how to land on Mars, collect the samples, launch from Mars (which has never been done before) and rendezvous with another capsule that will bring the precious samples to Earth.

Sample return is a complex, very costly and technologically high stakes venture. Best case scenario, it is not expected to bare fruit until some years into the 2030s.

But to those who know Mars best, it is the necessary path forward to a much fuller writing of the Mars water story and the intertwined question of whether Mars could have ever given rise to life.

One Reply to “”

Comments are closed.