For reasons all too regrettable, it seems appropriate today to highlight the extensive work being done in France and by French scientists to move forward the science of exoplanets.

The American public tends to view space observatories and exoplanet research as largely the domain of NASA and our nation. While we are leaders for sure, others are adding considerably to the field and to the world’s knowledge. And few nations have been as involved in the search for faraway worlds and efforts to understand them than France, and the work there will clearly continue.

“The French have been major contributors in the exoplanet field,” said David Latham, a senior astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who has worked a lot with French colleagues. “It’s spanned several decades now — from the detection of our first exoplanet (51 Pegasi b) on a French telescope to the large number of talented young French exoplanet researchers you see everywhere today.”

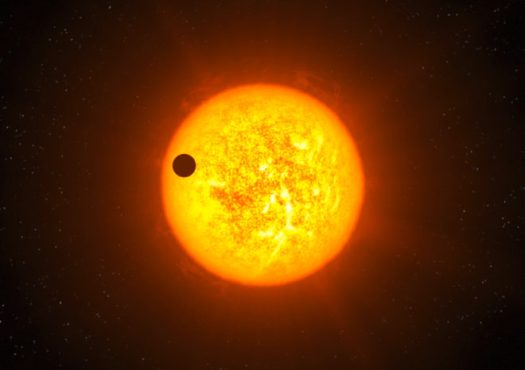

Probably the greatest single French contribution to exoplanet study has been the five-year run of the CoRoT (Convection, Rotation, and planetary Transits) spacecraft. Launched in 2006 – three years before our Kepler Space Telescope – it pioneered the space-borne detection and initial characterizing of exoplanets using the transit method. CoRoT was not as powerful as Kepler in its ability to see into space, but it did end up finding more than 30 exoplanets using the same transit method of detection, with more than 100 additional planet candidates awaiting confirmation.

One of its most significant contributions was the discovery of the first definitively rocky exoplanet, COROT-7b. Less than twice Earth’s size and roughly the same density, it orbits its Sun-like star every 20 hours and is so likely molten. It was a surprising discovery for a telescope designed to find Jupiter-size planets.

The satellite mission was a collaboration of the French space agency, the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) and European space agencies, but France paid much of the cost and French scientists and engineers designed and made most of the instruments.

The head of the CoRoT exoplanet program was Magali Deleuil from Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille. Her handling of the project was so strong that she was appointed to oversee two upcoming European exoplanet missions – Cheops (scheduled to launch in 2017, with Swiss leadership) and Plato (planned for 2024 and led by Germany.)

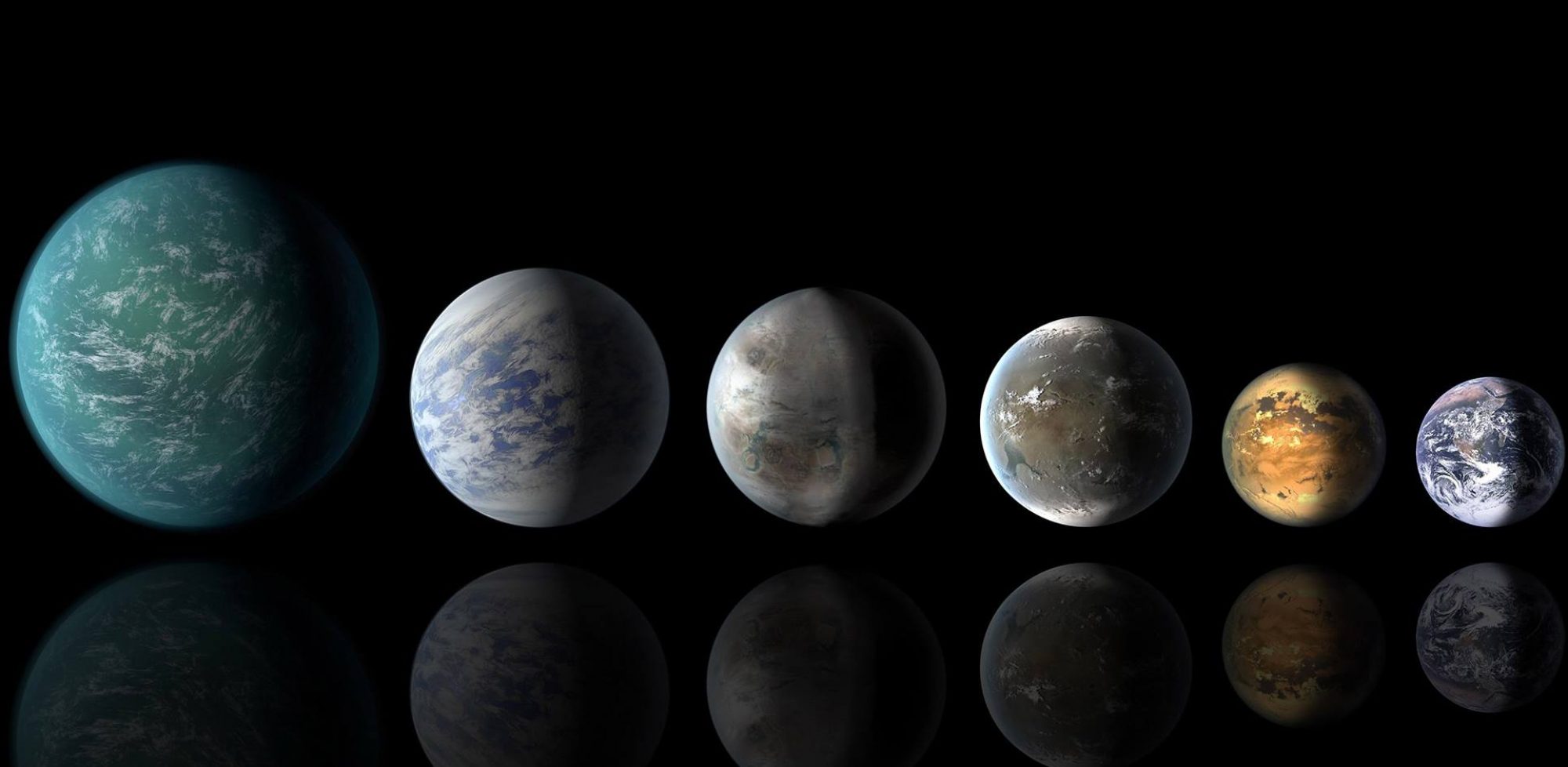

Cheops (the CHaracterizing ExOPlanet Satellite) is designed primarily to further study exoplanets identified by CoRoT and Kepler and measure their radii, while the goal of the more sophisticated Plato (Planetary Transits and Oscillations of stars) mission is to find planets like Earth, in terms of both size and potential habitability. Plato will have a much larger field of view than Kepler, and so will be able to see far more stars and exoplanets.

The principal investigator for CoRoT was Annie Baglin, senior researcher at the Paris Observatory. Her main field of research is stellar physics and her major interest is now stellar seismology – the deep internal vibrations that regularly shake our sun and others. These dynamics of stars have become increasingly important as a method to understand what is going on in their interiors, and to tease out some aspects of their composition.

In 1964, France became one of the founding members of the European Southern Observatory, a consortium now of 17 nations that has together planned, funded and completed construction of four of the most important ground-based telescopes in the world. All are in Chile, and have made significant contributions to exoplanet research. (That observatory where 51 Peg was discovered is the Haute-Provence Observatory, which opened more than seventy years in southeastern France and is still operating.)

Another ESO telescope is scheduled to come on line in 2024, and it will have the largest mirror by far in the world – more than 39 meters across. The European Extremely Large Telescope has as one of its primary goals the detection and characterizing of exoplanets.

France has also been the lead European nation in the development and operation of the Ariane family of rockets, and an Ariane 5 will launch the James Webb Space Telescope into space in 2018.

And there has also been a steady flow of French exoplanet researchers to American institutions, and vice versa. Francois Forget, for instance, has worked on climate modeling of exoplanet atmospheres at the NASA Ames Research Center in California, and is now a senior researcher at the Institut Pierre Simon Laplace Universite in Paris. His work on exoplanet atmospheres is highly respected world.

American Sean Raymond of Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux in France, has seen that exoplanet focus in action.

“There is indeed a lot of exoplanet research in France,” he said. “In some subjects such as planet formation, I would say that France is doing as much or more than any other country.”

Similarly, David Latham’s CfA published results last week about a planet with a radius only 1.2 times that of Earth, and both relatively close to our solar system and with a star that gives it good definition. The planet, Gliese 1132b, is expected to be a prime candidate for study well into the future.

As Latham pointed out, five of the co-authors were from France.

I’ve known the French have been involved with astronomy for quite some time, but never realized to what extent. Thanks to this article, I consider myself updated! I’ve had an abiding passion for science, particularly astronomy ever since I was old enough to look up and realize what stars really are, but I’ve never put much effort into knowing who did what – my passion was always for the discoveries and advancements by themselves, regardless of who contributed what. But I guess it’s high time to start taking note, and thus giving credit where credit is due. Vive la France !

LikeLike

This article misses out quite a lot. For example, the French team based around the SOPHIE spectrograph at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence have been very active in radial-velocity follow-up of candidates from transit surveys. Thus they are co-authors on the discovery papers for over 30 WASP transiting exoplanets, and quite a few Kepler exoplanets.

LikeLike

Yes! Alexandre Santerne and collaborators have been observing the giant planet candidates identified by the Kepler spacecraft with SOPHIE, sorting out which are bonafide planets and which are astrophysical false positives. Such a valuable contribution!

LikeLike