The Hayabusa2 sample return capsule returning to Earth. The bright streak in the sky is the capsule, shock heated as it enters the Earth's atmosphere. The bright lights on the ground are buildings. (JAXA) In the early hours of December 6, 2020, what appeared to be a shooting star blazed across the sky above the …

Touching the Sun

The Parker Solar Probe is the stuff of superlatives and marvels. Later this week, it will pass but 5.3 million miles from the sun -- much closer than Mercury or any other spacecraft have ever come -- and it will be traveling at a top speed of 101 miles per second, the fastest human-made object …

Japan’s Hayabusa2 Mission Returns to Earth

Fireball created by the Hayabusa2 re-entry capsule as it passes through the Earth's atmosphere towards the ground (JAXA). In the mission control room in Japan, all eyes were fixed on one of the large screens that ran along the far wall. The display showed the night sky, with stars twinkling in the blackness. We were …

Continue reading "Japan’s Hayabusa2 Mission Returns to Earth"

Standing on an Asteroid: Could the Future of Research and Education be Virtual Reality?

https://videopress.com/v/SgQvMH55?preloadContent=metadata Scenes from the virtual reality talk on Hayabusa2 with students from the Yokohama International School. Each student has a robot avatar they can use to look around the scene, talk with other people and interact with objects. (OmniScope) Have you ever wondered what it would be like to stand on an asteroid? A rugged …

Planetary Protection and the Moons of Mars

Sometime in the early to mid-2020s, the capsule of the Japanese Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission is scheduled to arrive at the moons of Mars – Phobos and Deimos. These are small and desolate places, but one goal of the mission is large: to collect samples from the moons and bring them back to Earth. …

Continue reading "Planetary Protection and the Moons of Mars"

Japan’s Mission to the Martian Moons Will Return a Sample From Phobos. What Makes This Moon So Exciting?

Artist impression of JAXA's MMX spacecraft around Mars (JAXA). Japan in planning to launch a mission to visit the two moons of Mars in 2024. The spacecraft will touchdown on the surface of Phobos, gathering a sample to bring back to Earth. But what is so important about a moon the size of a city? …

Hayabusa2 Snatches Second Asteroid Sample

Artist impression of the Hayabusa2 spacecraft touching down on asteroid Ryugu (JAXA / Akihiro Ikeshita) “1… 2… 3… 4…” The counting in the Hayabusa2 control room at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Institute of Space and Astronautical Sciences (JAXA, ISAS) took on a rhythmic beat as everyone in the room took up the chant, their …

Continue reading "Hayabusa2 Snatches Second Asteroid Sample"

Japan’s Hayabusa2 Asteroid Mission Reveals a Remarkable New World

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-3hO58HFa1M The Hayabusa2 touchdown movie, taken on February 22, 2019 (JST) when Hayabusa2 first touched down on asteroid Ryugu to collect a sample from the surface. It was captured using the onboard small monitor camera (CAM-H). The video playback speed is five times faster than actual time (JAXA). On March 5 the Japan Aerospace Exploration …

Continue reading "Japan’s Hayabusa2 Asteroid Mission Reveals a Remarkable New World"

The Gale Winds of Venus Suggest How Locked Exoplanets Could Escape a Fate of Extreme Heat and Brutal Cold

More than two decades before the first exoplanet was discovered, an experiment was performed using a moving flame and liquid mercury that could hold the key to habitability on tidally locked worlds. The paper was published in a 1969 edition of the international journal, Science, by researchers Schubert and Whitehead. The pair reported that …

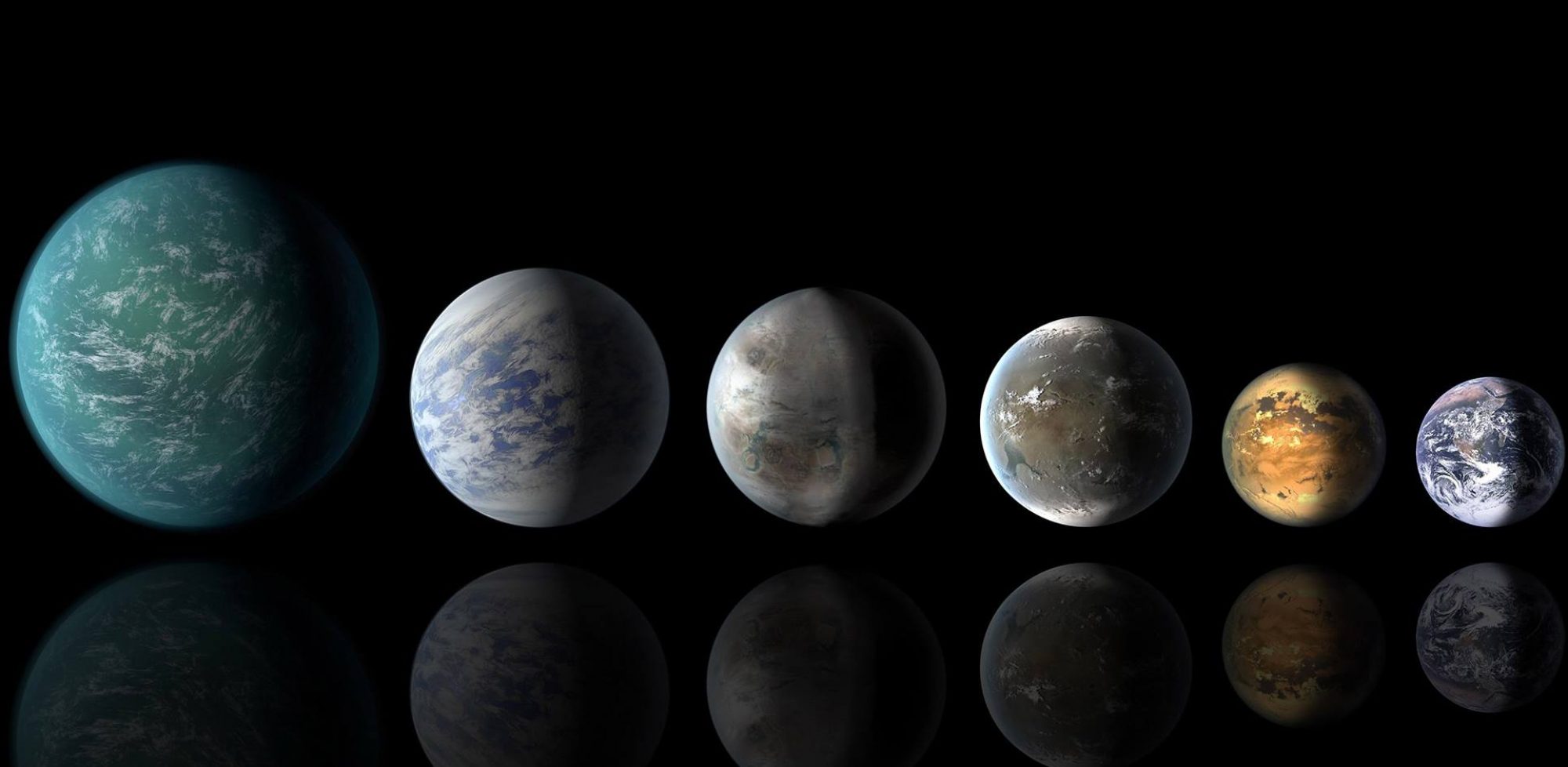

What Would Happen If Mars And Venus Swapped Places?

What would happen if you switched the orbits of Mars and Venus? Would our solar system have more habitable worlds? It was a question raised at the “Comparative Climatology of Terrestrial Planets III”; a meeting held in Houston at the end of August. It brought together scientists from disciplines that included astronomers, climate science, …

Continue reading "What Would Happen If Mars And Venus Swapped Places?"