Spending time immersed in the world of exoplanets raises questions of all sorts, and some lead down unexpected pathways.

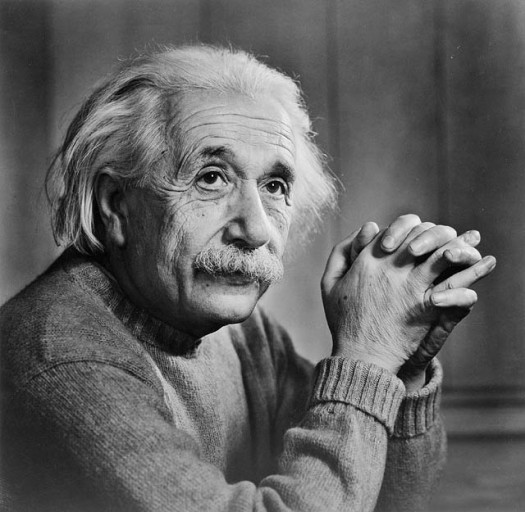

In the aftermath of the 100th anniversary of the publication of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, another part of the great man’s legacy has entered into my life in a way both surprising and satisfying. I’ll never come close to understanding the deeper currents of Einstein’s relativity, but I have found an entirely accessible and compelling clarity in his views on another domain of great importance to him: his concept of “cosmic religion.”

There was a time when these views were widely debated, and Einstein was regularly asked to address questions about religion. Those days are long gone and his thinking about religion seems to be considered naive by many and rather passe — in a similar vein as his refusal to accept some of the tenets of the quantum physics that he helped establish.

But then again, maybe Einstein will prove to have been once again ahead of the curve with his cosmic spirituality.

As might be anticipated, Einstein’s views on religion were largely his own invention. He rejected the idea of a personal god as fantasy, did not see any value in the intercession of a priestly or rabbinical class, and dismissed as unnecessary a morality created and enforced by organized religion.

Yet he also fiercely rejected the assertion that he was an atheist, just as he dismissed the perceived necessity of a division between the realms of science and religion (as he saw religion, at least.)

As I understand it, he concluded that the very process of seeking to understand the world through disciplined science can and does create both a knowledge and a humility that lead many toward a life rich in transcendence. In fact, the “cosmic religion” that he saw as an essential advance on traditional religions was accessible primarily to scientists — at least at the time he was writing. Science was a pathway to understanding nature and the universe, and more.

How this all plays out is no doubt best described by Einstein himself:

“The human mind, no matter how highly trained, cannot grasp the universe. We are in the position of a little child, entering a huge library whose walls are covered to the ceiling with books in many different tongues. The child knows that someone must have written those books. It does not know who or how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written.

The child notes a definite plan in the arrangement of the books, a mysterious order, which it does not comprehend, but only dimly suspects. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of the human mind, even the greatest and most cultured, toward God.

We see a universe marvelously arranged, obeying certain laws, but we understand the laws only dimly. Our limited minds cannot grasp the mysterious force that sways the constellations.”

He described this transcendent force — that definitely was not a God in the Abrahamic tradition — to an interviewer in 1930, when he was 51. Some years later he wrote in “The World as I See It:”

“I cannot conceive of a God who rewards and punishes his creatures, or has a will of the type of which we are conscious in ourselves. An individual who should survive his physical death is also beyond my comprehension, nor do I wish it otherwise… . Enough for me the mystery of the eternity of life, and the inkling of the marvelous structure of reality, together with the single-hearted endeavour to comprehend a portion, be it never so tiny, of the reason that manifests itself in nature.”

And, in a less philosophical vein:

“He who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead.”

All this was thought and said and written in the relatively early days of the modern scientific exploration of the universe. Imagine the “awe” an Einstein would experience after learning about the outpouring of discovery that followed him.

Reading Einstein on cosmic religion didn’t feel like a revelation to me but rather like a coming home to a place I oddly recognized but had never actually visited before.

I was raised in a secular Jewish household where bar mitvahs and seders were absent. I recall after my Catholic father-in-law died telling my bereft wife that the two of them would meet again. I believed it that day but not for long after. And while living in India as a correspondent, I was exposed to Buddhist thought that I found very attractive, but I was never moved to connect with a Buddhist community. I’ve long felt spiritual and transcendent tugs, but my life has been secular through and through, and I’ve been basically fine with that. No appealing alternatives showed up.

Then came science.

I had spent a good part of my five-decades-plus with only a limited interest in the processes and results of science; the exception being a childhood spurt of booklet writing about dinosaurs, weather, space that I and a friend sold door-to-door. I later became a journalist and for three decades wrote mostly about our collective tragedies and vices, large and small. And then an editor asked me a decade ago if I would cover NASA and space. I initially said no way but then relented.

Soon I was immersed in the worlds of black holes and exoplanets, of the possibilities of life beyond Earth and the reality of hyper-extreme life on Earth. Many worlds, indeed. My gradually increasing familiarity with these subjects and phenomena, and the people pushing the boundaries of understanding about them, has been thrilling. And it has invited – required, actually – a newfound opening to the grandeur of our inheritance.

Earlier this year I picked up an Einstein biography and was intrigued by this idea of “cosmic religion.” First I was attracted by his unblinking rejection of current religions and what he described as a “feeling of deep and painful disappointment at what one sees” from them throughout much of the world. I might not go that far, but it was bracing to see that view aired circa 1948.

But it was that positive side of what Einstein presented that really pulled me in: science as a pathway to transcendence. No faith or belief needed. Reason, replicable experimentation in labs and the mind, and creative leaps and courage could open realms more marvelous than what any traditional religion offered me. And no, Einstein said, there was no larger point, no particular meaning to this wondrous show. There’s just the show.

A strange way to come to “religion,” but also oddly consistent with the life I’ve lived, events I’ve witnessed, my particular place in time.

So for me at least, Einstein was onto something with his cosmic religion. In his writings he described that religious plane as pretty much the domain of practicing scientists, and I definitely am not of that world. But even Einstein could not have imagined the democratizing of scientific knowledge and curiosity that has subsequently taken place. I’m certainly no Einstein, but I’m moved by what he said and wrote. And I’ve come to think that it’s not only me.

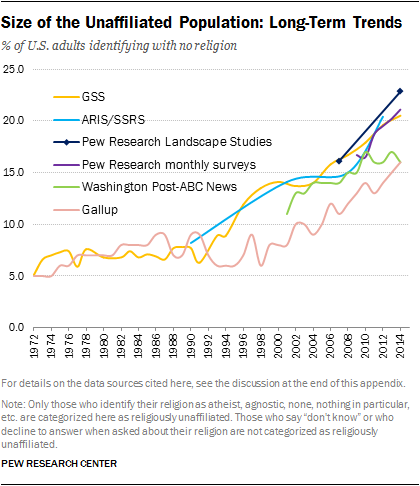

This past summer, the Pew Research Center’s “U.S. Religious Landscape” survey documented a pretty steep decline in the percentage of Americans self-defining as part of a religious tradition, while the percentage of people who were atheist, agnostics, or “no particular affiliation ” was rising fast – up to almost 23 percent of the population.

I was particularly intrigued by this burgeoning group of so-called “nones,” who, it turns out, describe themselves as “spiritual” at a rate only a bit lower than traditionally religious people. They also were as equally likely to experience a weekly (or more frequent) sense of awe and wonder about the universe as traditionally religious people – just under 50 percent from both groups. And among atheists and agnostics, a small but fast growing group, the percentage reporting feelings of “spirituality” were particularly high.

Is this a sense of something akin to “cosmic religion” expressing itself? Does the rise of spirituality and awe in the population while traditional religion is declining signal a meaningful switch in how Americans approach the world and its mysteries? The Pew research does not directly address these questions, but indirectly the responses are certainly suggestive.

The reported shift certainly isn’t happening because people are rushing out to read about Einstein’s religious views. But wouldn’t it be fitting if his unconventional and once controversial spirituality – like his many radical scientific theories that led to discoveries even well after his death — proved to be useful, on target and really quite timely?

Thank you, I had no idea that you were a templeton fellow. [ http://www.templeton.org/templeton_report/20080611/TempletonReport20080611.pdf ]

Now I feel fooled, I don’t condone mixing science with magic and mysticism (outside of the social study of religion, of course). yet I have commented here earlier, on what in effect can’t be distinguished from yet another outlet for templeton’s insidious idea of taking support for religion in science of all places. (Magic and mysticism – even einstein’s – isn’t scientific useful, and societal usefulness is fuzzy – is smoking “useful”?)

Well, it will likely be the last time, this site is now Removed from my feed.

LikeLike

I meant “invidious” Idea of course. (English isn’t my first language.)

LikeLike

[ I also now note there is a tie between the name for the blog and Templeton : https://www.templetonpress.org/content/many-worlds ]

LikeLike