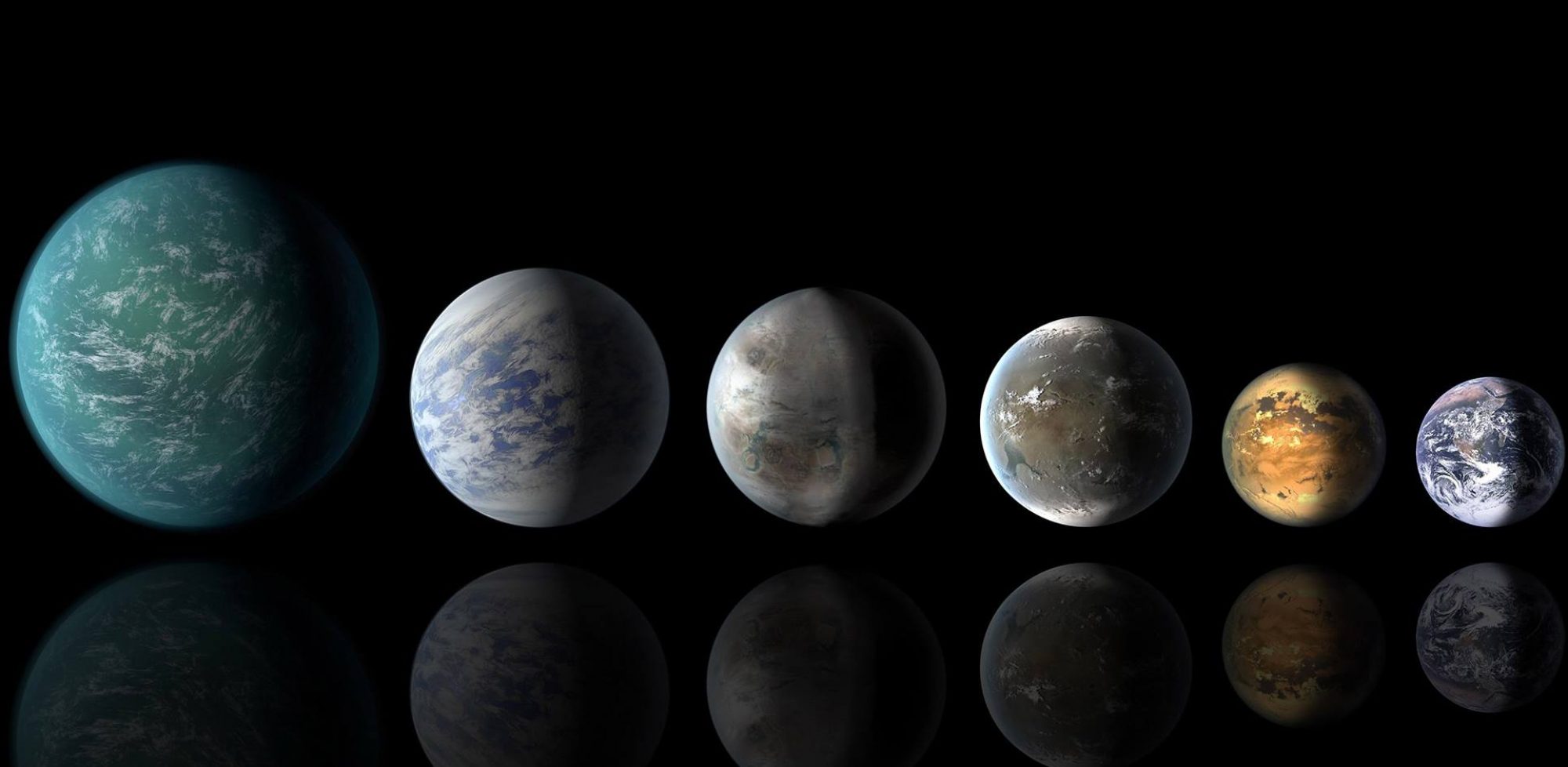

One of the more persuasive arguments in favor of the potential existence of life beyond Earth is that the well-known chemical building blocks of that life are found throughout the galaxy. These chemical components aren't all present in all examined solar systems and planets, but they are common and behave in ways familiar to scientists …

Continue reading "Many Planets Form in a Soup of Life-Friendly Organic Compounds"