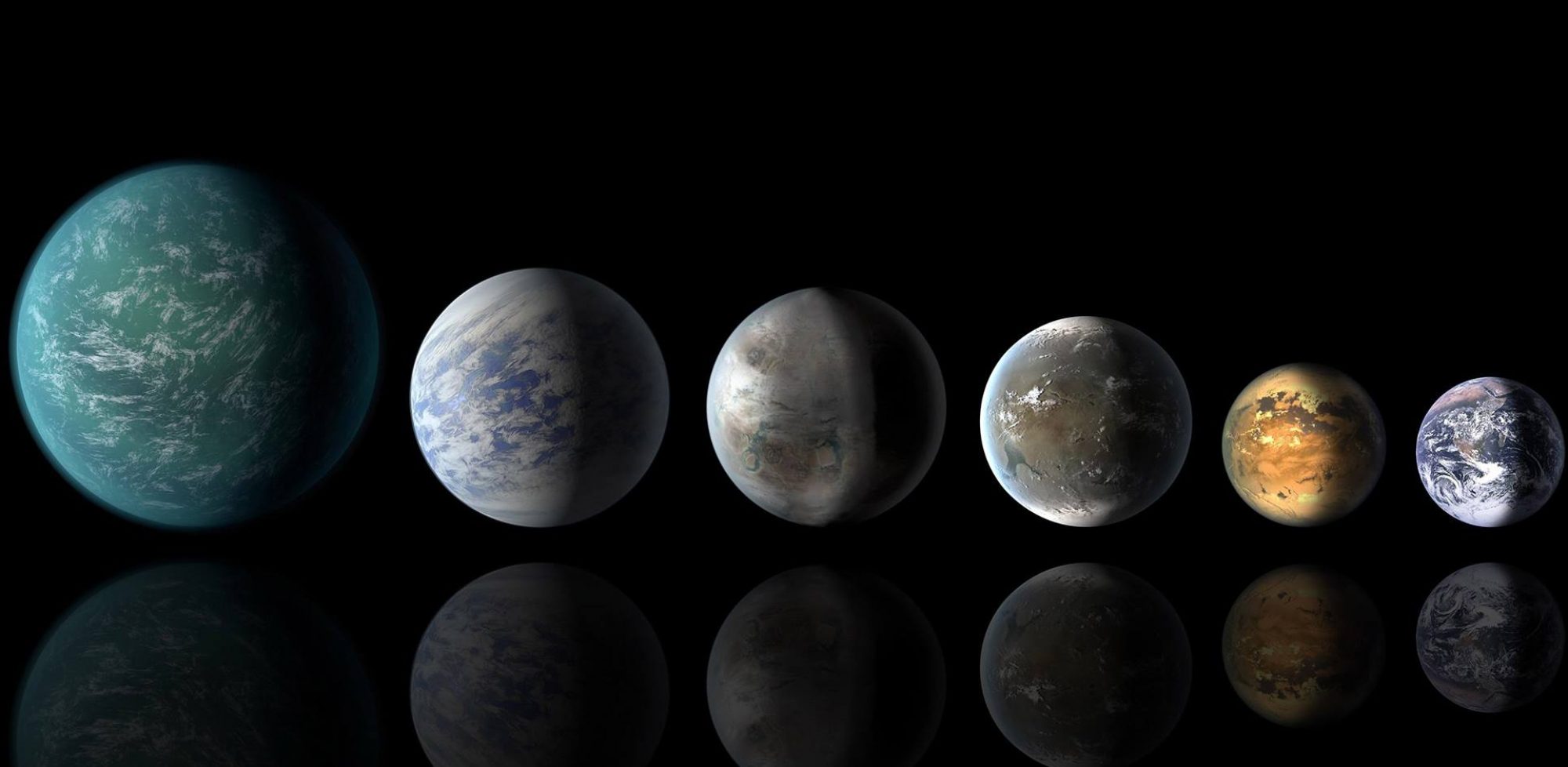

This is a golden era for space and planetary science, a time when discoveries, new understandings, and newly-found mysteries are flooding in. There are so many reasons to find the drama intriguing: a desire to understand the physical forces at play, to learn how those forces led to the formation of Earth and ultimately us, …

Continue reading "Some Spectacular Images (And Science) From The Year Past"