I hope you will indulge me in this foray into a very different look at the many worlds in which we live.

My father is being buried today. It is no tragedy; he lived to almost 97 and had a full life. But still…

As all of you have no doubt experienced in one way or another, there is a huge disconnect between the emotions we feel individually about a newcomer to our world or a departing elder and the arrival and departure of those we don’t know at all.

The birth of a loved child is as glorious as most anything can be. And yet it is, in the larger picture, totally banal. I found this figure: By 2011, an estimated 107,602,707,800 humans had been born since the emergence of the species.

Same with death. The death of a loved elder is a profound event. And yet it, too, is banal. One hundred billion of those born have also died.

There are a handful of exceptions to this dual reality. These births and deaths (and lives) are not viewed as banal but as historically important. You can pick your own people for that list, but I bet they will be a group of people both very good and very bad, many of them talented and all of them charismatic.

But for the rest of us, a particular birth and death are of enormous importance to very few. It’s a kind of background noise.

Why am I writing about this now?

Clearly because I’m grieving and trying to make sense of the suffering and passing of my father.

But also because that grief — and the absence of grief all around me in New York City where he lived — speaks to that weird relativity in the emotional universe. When you look closely at what reality is, the picture is very different from how things may feel inside.

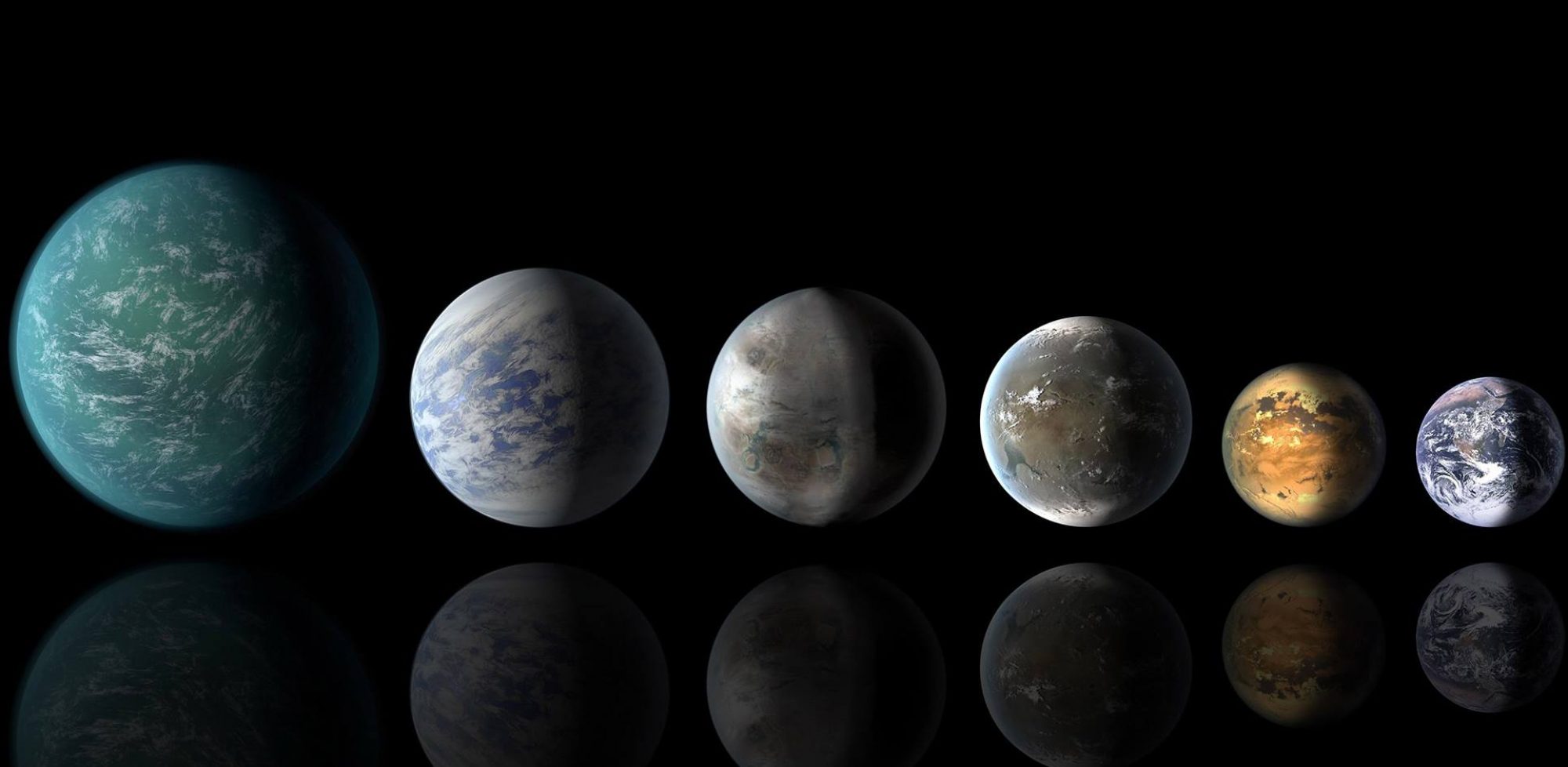

This is a dichotomy I’ve had to embrace as I learn and write about the cosmos. Our human view of the world is, well, often quite lacking in perspective.

Our sense of time is another example. We humans live within a story line where a life of 97 years is a very long one. Although there are an increasing number of long-lived people — almost two million above age 90 in the United States — they remain a tiny percentage of the population.

In terms of Earth’s 4.5 million years of geological time, my father’s 96 years is less than a blip. And in astronomical time — the 13.7 billion years of the universe — they are completely inconsequential.

Our human lifetimes matter so much to us. But in the reality of time and space as they truly exist, those lives mean virtually nothing. Yet we persist in our great joys and sorrows. “All the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players,” wrote one of those people whose name and legend does live on. “They have their exits and their entrances, and one man in his time plays many parts…” I think my father would appreciate this stepped-back approach to his passing.

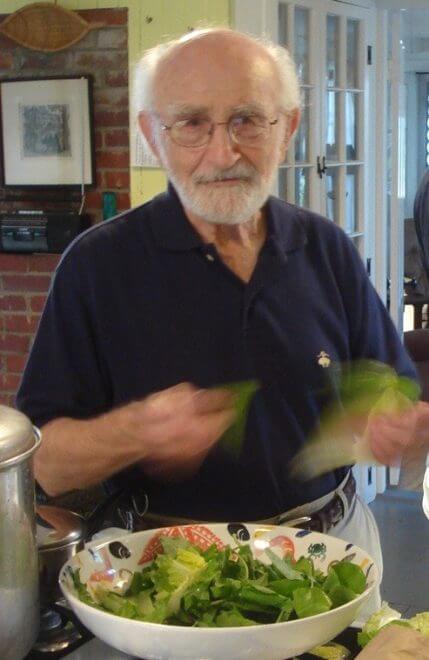

He was born poor in the South Bronx and became a soldier, student, artist, professor, poet and voracious reader. His background included virtually no science study, but as I wrote more about space and life origins, he found those subjects to be increasingly interesting. (They were a welcome reprieve for me from the political discussions he was inclined to wage in a take-no-prisoners style.)

He was not a religious man, but he did enjoy thinking and reading about subjects ranging from the beginning of the cosmos to theories of quantum life. I don’t think he would ever use this word, but he sought a kind of cosmic transcendence.

This was especially so after the passing of his wife of 63 years. He was nearly crushed by his grief, but he gradually put together a life that continued with stubborn and hopefully satisfying independence for 11 years.

He told me for several years that he didn’t fear death. He didn’t want to die and went to many doctors to try to keep going. But he said he was ready to accept the end, and in his final weeks and days I came to see that he was — especially as he lost his treasured independence and endured a not inconsiderable amount of suffering.

He slowly left after a week of refusing almost all food and water. I’m told it’s a kind of animal path to dying. (No disrespect here, as we are animals, of course.) And I think such a path is no tragedy, especially given his good fortune to have had almost 97 years on Earth.

I wrote a column early in my tenure at Many Worlds about Einstein and his ideas about “cosmic religion.” In it, I wrote about that part of Einstein’s thinking that gets less attention than it seems to deserve, to me at least. And as I was thinking about my father’s passing, Einstein’s thoughts on cosmic religion came back to me.

No god, no unresolvable mysteries, no dogma. Instead the wonderful and punishing laws of nature and the cosmos, and our good fortune to have some time living in them as human beings. A kind of clear-eyed transcendence without all the religious trappings.

Thoughts of clear-eyed transcendence brought back to mind the most searing and surprising death and aftermath that I’ve witnessed. When I was a reporter at The Philadelphia Inquirer, a charming young woman and her reporter husband were finally going to have a long-desired baby. Well into the pregnancy, as I remember it, the woman starting getting very sick and was ultimately diagnosed with a fast-spreading cancer.

It was brutal, but she hung on and gave birth. And then a few days later she died.

The entire Inquirer staff came to her funeral, and her husband got up to speak. None of us knew what to expect, what someone in his place could possibly say.

But speak he did, and what he had to say was powerfully moving and instructive. Yes, he had felt despair and anger at the awful turn of events, and, yes, what faith he had was shattered.

Then he spoke as if transported about the unexpected understanding that had come to him.

The death was an absolute tragedy and hideously unfair. But out of it had come a beautiful, healthy boy. Despite the horrible twist of fate, something precious had arrived. The mother’s strength and grit had allowed a longed-for baby to survive.

And the husband ended with this reality lost in the grief: had his wife not been pregnant, she still would have died of cancer. But she would have died without a lovely child delivered to the world.

Grief and joyful transcendence. There was not a dry eye in the huge crowd and not a heart that had not been lifted.

My father’s death will effect far fewer people than the one I just described. The emotional punch of his passing has less force because he lived fully and because so many of his contemporaries are gone.

But the emotional dichotomy is still there and cries out for transcendence. Each life is so important and yet so unimportant. How do we make sense of that?